Charles W. Lamb Jr, M.J. Neeley Professor of Marketing, M.J. Neeley School of Business, Texas Christian University, Fort Worth, Texas, USA

Top priority for many firms today. Research interest in branding continues to be strong in the marketing literature (e.g. Alden et al., 1999; Kirmani et al., 1999; Erdem, 1998). Likewise, marketing managers continue to realize the power of brands, manifest in the recent efforts of many companies to build strong Internet “brands” such as amazon.com and msn.com (Narisetti, 1998). The way consumers perceive brands is a key determinant of long-term business-consumer relationships (Fournier, 1998). Hence, building strong brand perceptions is a top priority for many firms today (Morris, 1996).

Despite the importance of brands and consumer perceptions of them, marketing researchers have not used a consistent definition or measurement technique to assess consumer perceptions of brands. To address this, two scholars have recently developed extensive conceptual treatments of branding and related issues. Keller (1993; 1998) refers to consumer perceptions of brands as brand knowledge, consisting of brand awareness (recognition and recall) and brand image. Keller defines brand image as “perceptions about a brand as reflected by the brand associations held in consumer memory”. These associations include perceptions of brand quality and attitudes toward the brand. Similarly, Aaker (1991, 1996a) proposes that brand associations are anything linked in memory to a brand. Keller and Aaker both appear to hypothesize that consumer perceptions of brands are multi-dimensional, yet many of the dimensions they identify appear to be very similar. Furthermore, Aaker’s and Keller’s conceptualizations of consumers’ psychological representation of brands have not been subjected to empirical validation. Consequently, it is difficult to determine if the various constructs they discuss, such as brand attitudes and perceived quality, are separate dimensions of brand associations, (multi-dimensional) as they propose, or if they are simply indicators of brand associations (uni-dimensional).

A number of studies have appeared recently which measure some aspect of consumer brand associations, but these studies do not use consistent measurement techniques and hence, their results are not comparable. They also do not discuss the issue of how to conceptualize brand associations, but focus on empirically identifying factors which enhance or diminish one component of consumer perceptions of brands (e.g. Berthon et al., 1997; Keller and Aaker, 1997; Keller et al., 1998; Roedder-John et al., 1998; Simonin and Ruth, 1998). Hence, the proposed multi-dimensional conceptualizations of brand perceptions have not been tested empirically, and the empirical work operationalizes these perceptions as uni-dimensional.

Practical measurement protocol. Our goal is to provide managers of brands a practical measurement protocol based on a parsimonious conceptual model of brand associations.

The specific objectives of the research reported here are to:

- test a protocol for developing category-specific measures of brand image;

- examine the conceptualization of brand associations as a multi-dimensional construct by testing brand image, brand attitude, and perceived quality in the same model; and

- explore whether the degree of dimensionality of brand associations varies depending on a brand’s familiarity.

In subsequent sections of this paper we explain the theoretical background of our research, describe three studies we conducted to test our conceptual model, and discuss the theoretical and managerial implications of the results.

Conceptual background

Brand associations

Importance to marketers and consumers. According to Aaker (1991), brand associations are the category of a brand’s assets and liabilities that include anything “linked” in memory to a brand (Aaker, 1991). Keller (1998) defines brand associations as informational nodes linked to the brand node in memory that contain the meaning of the brand for consumers. Brand associations are important to marketers and to consumers. Marketers use brand associations to differentiate, position, and extend brands, to create positive attitudes and feelings toward brands, and to suggest attributes or benefits of purchasing or using a specific brand. Consumers use brand associations to help process, organize, and retrieve information in memory and to aid them in making purchase decisions (Aaker, 1991, pp. 109-13). While several research efforts have explored specific elements of brand associations (Gardner and Levy, 1955; Aaker, 1991; 1996a; 1996b; Aaker and Jacobson, 1994; Aaker, 1997; Keller, 1993), no research has been reported that combined these elements in the same study in order to measure how they are interrelated.

Scales to measure partially brand associations have been developed. For example, Park and Srinivasan (1994) developed items to measure one dimension of toothpaste brand associations that included the brand’s perceived ability to fight plaque, freshen breath and prevent cavities. This scale is clearly product category specific. Aaker (1997) developed a brand personality scale with five dimensions and 42 items. This scale is not practical to use in some applied studies because of its length. Also, the generalizability of the brand personality scale is limited because many brands are not personality brands, and no protocol is given to adapt the scale. As Aaker (1996b, p. 113) notes, “using personality as a general indicator of brand strength will be a distortion for some brands, particularly those that are positioned with respect to functional advantages and value”. Hence, many previously developed scales are too specialized to allow for general use, or are too long to be used in some applied settings. Another important issue that has not been empirically examined in the literature is whether brand associations represent a one-dimensional or multi-dimensional construct. Although this may appear to be an obvious question, we propose later in this section the conditions under which this dimensionality may be more (or less) measurable.

Linked in memory to a brand. As previously noted, Aaker (1991) defines brand associations as anything linked in memory to a brand. Three related constructs that are, by definition, linked in memory to a brand, and which have been researched conceptually and measured empirically, are brand image, brand attitude, and perceived quality. We selected these three constructs as possible dimensions or indicators of brand associations in our conceptual model. Of the many possible components of brand associations we could have chosen, we selected these three constructs because they:

- (1) are the three most commonly cited consumer brand perceptions in the empirical marketing literature;

- (2) have established, reliable, published measures in the literature; and

- (3) are three dimensions discussed frequently in prior conceptual research (Aaker, 1991; 1996; Keller, 1993; 1998).

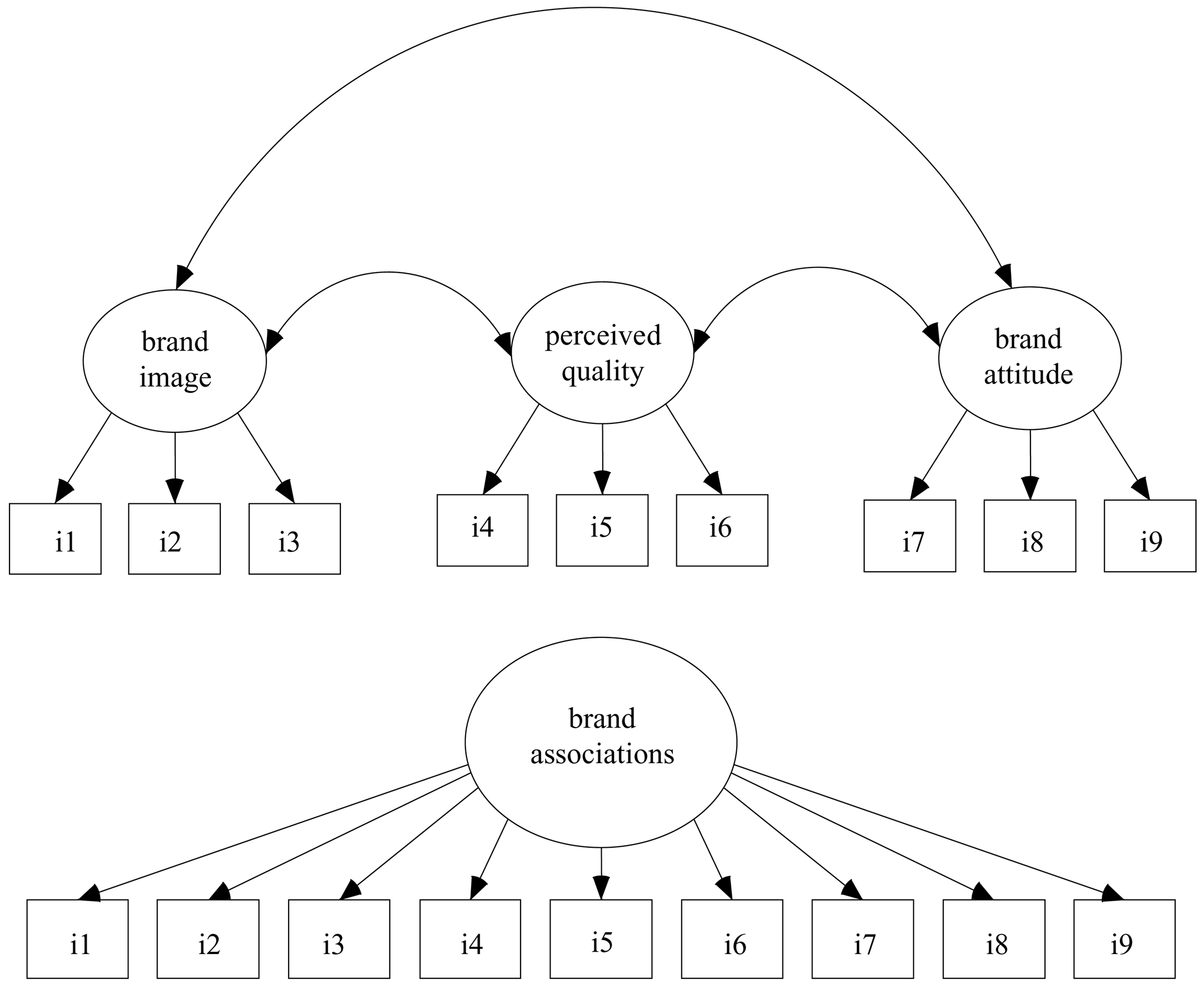

We conceptualize brand image (functional and symbolic perceptions), brand attitude (overall evaluation of a brand), and perceived quality (judgments of overall superiority) as possible dimensions of brand associations (see Figure 1).

Brand image, brand attitude, and perceived quality

Reasoned or emotional perceptions. Brand image is defined as the reasoned or emotional perceptions consumers attach to specific brands (Dobni and Zinkhan,1990) and is the first consumer brand perception that was identified in the marketing literature (Gardner and Levy, 1955). Brand image consists of functional and symbolic brand beliefs. A measurement technique using semantic differential items generated for the relevant product category has been suggested for measuring brand image (Dolich, 1969; Fry and Claxton, 1971). Brand image associations are largely product category specific and measures should be customized for the unique characteristics of specific brand categories (Park and Srinivasan, 1994; Bearden and Etzel, 1982).

Brand attitude is defined as consumers’ overall evaluation of a brand – whether good or bad (Mitchell and Olson, 1981). Semantic differential scales measuring brand attitude have frequently appeared in the marketing literature. Bruner and Hensel (1996) reported 66 published studies which measured brand attitude, typically as the dependent variable in research on product line extensions or advertising affects. Consumer attitudes toward brands capture another aspect of the meaning consumers attach to brands in memory which affects their purchase behavior.

Perceived quality is defined as the consumer’s judgment about a product’s overall excellence or superiority (Zeithaml, 1988; Aaker and Jacobson, 1994). For example, Sethuraman and Cole (1997) found that perceived quality explains a considerable portion of the variance in the price premium consumers are willing to pay for national brands. The perceived quality of products and services is central to the theory that strong brands add value to consumers’ purchase evaluations.

Related dimensions?. Brand image, brand attitude, and perceived quality have been used independently for many years to measure brand associations. However, no studies have yet been reported that concurrently studied these three constructs to see how and if they are related. Are these three separate, related dimensions or are they simply different indicators of brand associations? Figure 1 illustrates these competing hypotheses. We do not suggest that these three components are the only elements of brand associations – we recognize the complex nature of these consumer-based perceptions of brands – however, at the same time, they represent a parsimonious structure on which researchers can begin to address the important conceptual and empirical questions raised here.

We posit that brand image, brand attitude, and perceived quality behave as separate dimensions under some conditions and as one dimension under other conditions. Research in consumer psychology (e.g. Alba and Hutchinson, 1987; Walker et al., 1987) suggests that consumers who have more experience with a brand also develop more dimensions and categories in their deeper knowledge structures. We propose that consumers have more highly developed brand association structures for familiar brands than for less familiar ones, and hence are more likely to have multi-dimensional brand associations for familiar brands compared to less- or unfamiliar brands.

Method and results

Task and procedure

Scale development. Scale development was performed following the suggestions of Churchill (1979) and Zaichowsky (1985). The general approach entailed selecting a product that was relevant to the research subjects, preparing test advertisements as research stimuli, selecting scale items to measure brand image, brand attitude, and perceived quality, and collecting and analyzing the data. Advertisements were used as research stimuli to elicit brand associations for fictitious and real brands. Fictitious brand names are frequently used in brand association studies to heighten experimental control (Boush and Loken, 1991; Keller and Aaker, 1992). Three studies were conducted to prepare scale items, test them, extend the technique across product categories, and examine the dimensionality of brand associations. Fictitious brands were used in the first two studies to enhance experimental control during initial protocol testing. Real brands were used in the third study.

Study 1

The purpose of the first study was to test a protocol for developing product category specific measures of brand image. The other two constructs (brand attitude and perceived quality) have standardized measures which are generalizable across product categories. Brand image, however, requires the development of scale items that are product category specific (Dobni and Zinkhan, 1990). For example, scale items for measuring the image of a brand of handheld calculator would be different than those that would measure the image of a brand in the shampoo product category.

Unique associations. In some situations, brands in the same product categories do not even share brand image dimensions. For example, Timex watches are associated with functional dimensions whereas Rolex watches are associated with prestige (Park et al., 1991). According to Park et al. (1986), brand concepts position products in the minds of consumers and differentiate given products from other brands in the same product category. For example, prestige brand names may be stored together under a superordinate concept category such as luxury and status, while functional brand names may be stored primarily under their respective product class categories along with their brand concepts (Park et al., 1989). Broniarczyk and Alba (1994) add that brands in broad product association categories such as function or prestige may even have unique associations.

These findings indicate that the broadest appropriate basis for conducting brand image studies is the product category. In many situations the appropriate basis is competitors within a market segment. In some cases, association may even be brand-specific (Broniarczyk and Alba, 1994). The protocol we tested could be used at the product category, market segment, or individual brand level, depending on product/market characteristics.

A fictitious brand. As a pretest for Study 1, 35 undergraduate students were asked to write down any ideas, feelings, or attitudes that they associate with a handheld calculator. A handheld calculator was selected because it is meaningful to the research subjects and many of them have had purchase experience in the product category. The open-ended responses were tabulated and the 17 most frequently named terms were used to develop 17 semantic differential items, as suggested by Dolich (1969). A simple advertisement showing a picture of the product, its fictitious brand name, and a short copy block describing its basic features and benefits was developed. A fictitious brand was used in order to avoid the influence of established brand associations on the results. A total of 533 undergraduate students were used as main sample research subjects. Each subject was asked to view the advertisement for 30 seconds and then to complete the 17 scale items based on the brand described in the advertisement. They were also asked to complete a scale measuring their intent to purchase the calculator in the advertisement.

Study 1 results

The main sample responses for Study 1 were used to develop a measure of brand image. Coefficient alpha and exploratory factor analysis were used to reduce the number of items from 17 to five. Many of the items were similar and measured nearly identical attributes, which was evident in the exploratory factor analysis. The objective in this development was not to produce the highest coefficient alpha possible, but to tap different elements of brand image while maintaining an acceptable level of reliability (greater than 0.70). Accordingly, one item from pairs or groups of redundant items (e.g. helpful and useful; compact and handy) was eliminated. The final five scale items measured the following associations: accurate, useful, attractive, exciting, and handy. The coefficient alpha for these five items was 0.71. The sum of these five items was correlated with the intent to purchase measure in order to check the reduced scale’s predictive validity. The correlation was high (0.48), and significant (p < 0.01). Based on these results, it was concluded that the protocol used to measure brand image was satisfactory.

Study 2

One objective of Study 2 was to examine whether or not the protocol tested in Study 1 could successfully measure brand image for a brand in a different product category. A second objective was to investigate the dimensionality of the brand association construct by including all three measures. Specifically, the two competing conceptualizations of brand association shown in Figure 1 were examined in Study 2.

Identification of product category. Various products were pre-tested to identify a product category relevant to the main study population, undergraduate students. Shampoo was selected based upon its usage rate (73 per cent) and frequency of purchase (5.3 times per year). The pre-test subjects were also asked to provide brand image items (ideas, feelings, and attitudes) for shampoo, as in Study 1.

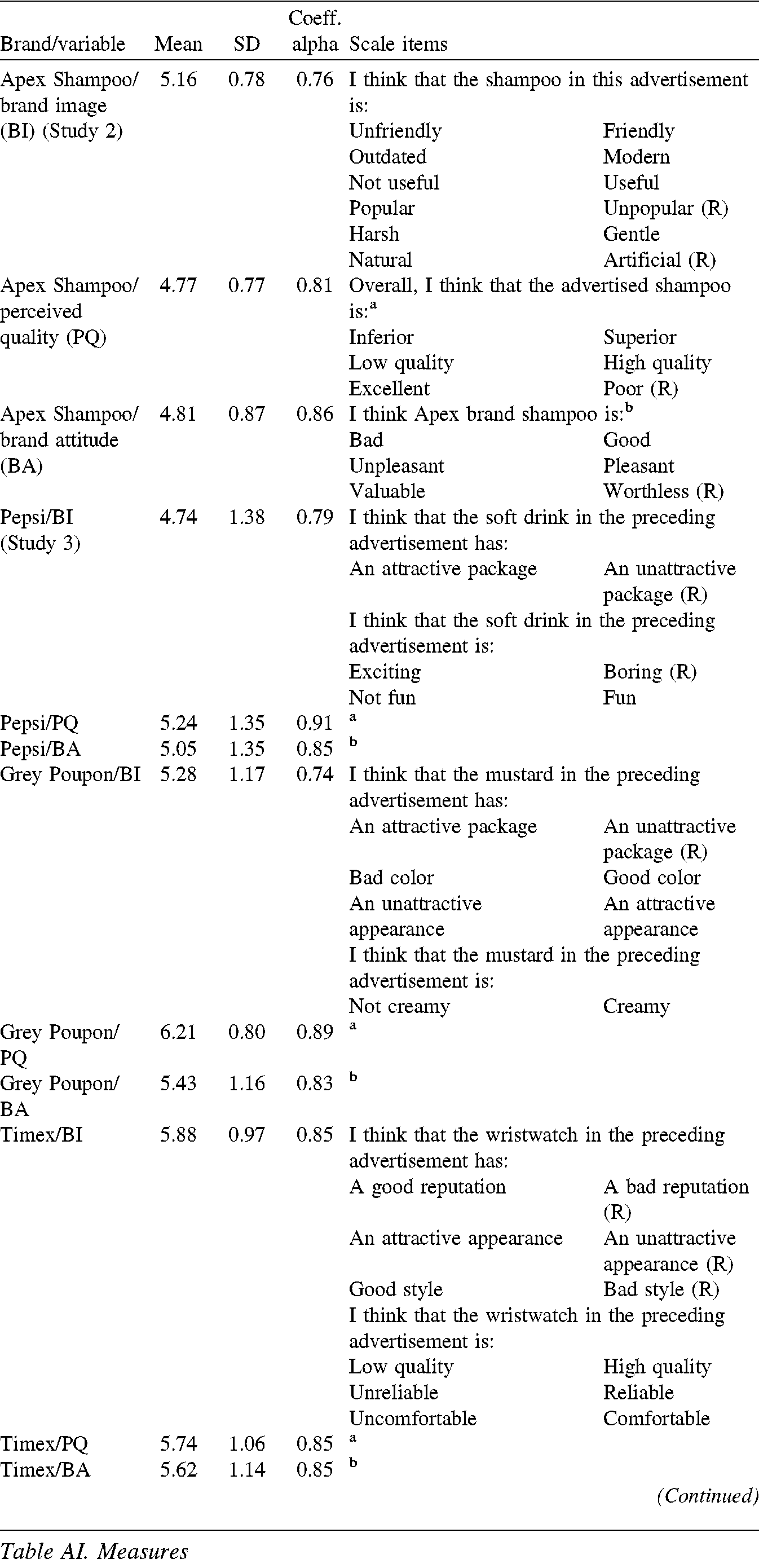

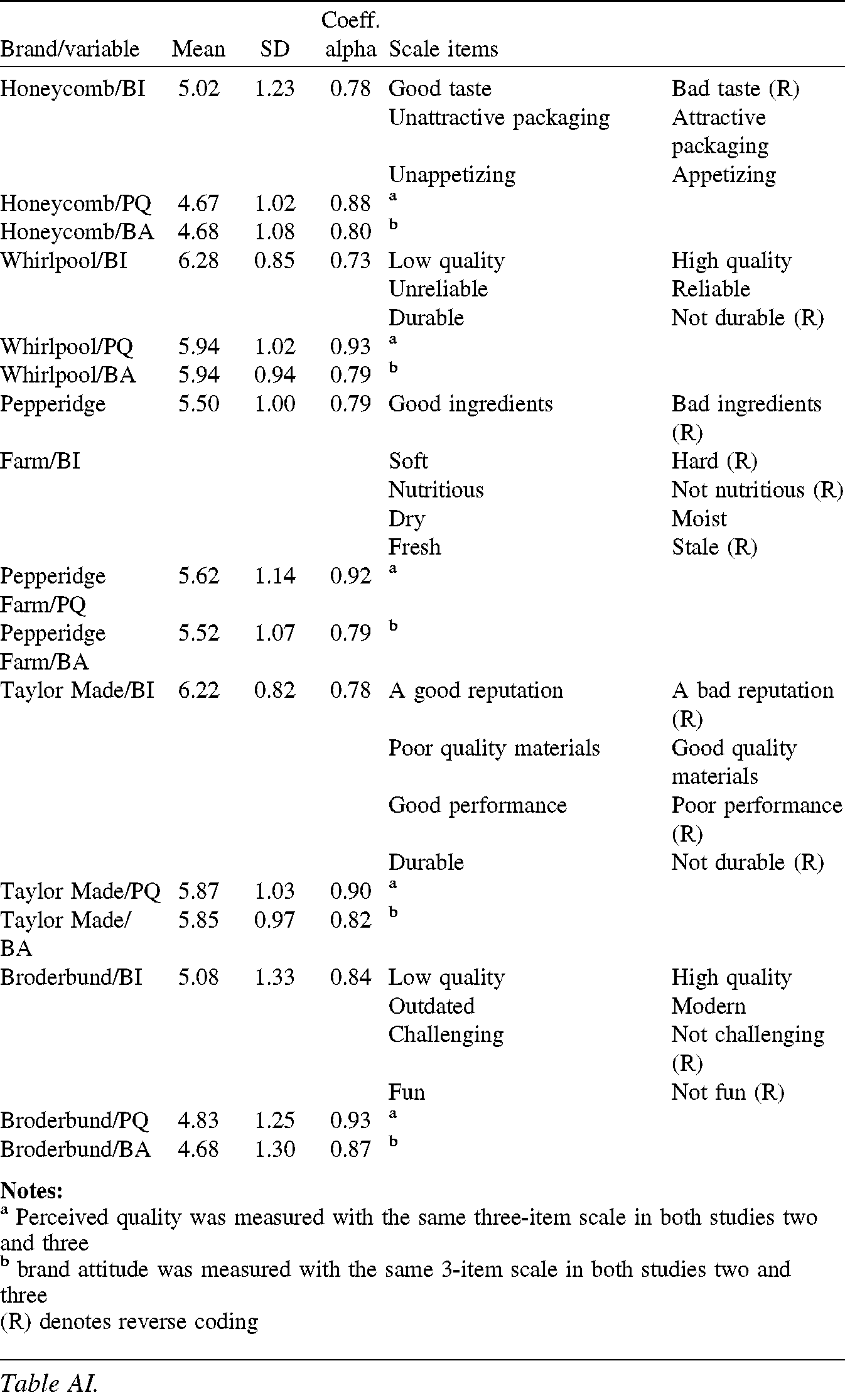

Following the protocol tested in Study 1, these items were used to develop a measure of brand image. The final set of six brand image items were friendly/unfriendly, modern/outdated, useful/not useful, popular/unpopular, gentle/harsh, and artificial/natural. Scale items for perceived quality (Keller and Aaker, 1992) and brand attitude (Zinkhan et al., 1986) were drawn from the marketing literature. The three most commonly used semantic differential scale anchors were used for each of these constructs. For perceived quality, the semantic differential anchors were (based on the lead-in statement “I think that the advertised product is:”) superior/inferior, excellent/poor, and good quality/poor quality. For brand attitude, the items were (based on the lead-in statement “I think this brand is:”) good/bad, pleasant/unpleasant, and valuable/worthless (see Appendix for scale items). A fictitious brand was chosen so that previous brand associations would not affect the measurement process, and a simple, yet professional advertisement was developed as a research stimulus. Subjects for the main study were 105 undergraduate students. Each subject was shown an advertisement for the shampoo product and asked to look at it for 30 seconds. They were then asked to complete the questionnaire.

Study 2 results

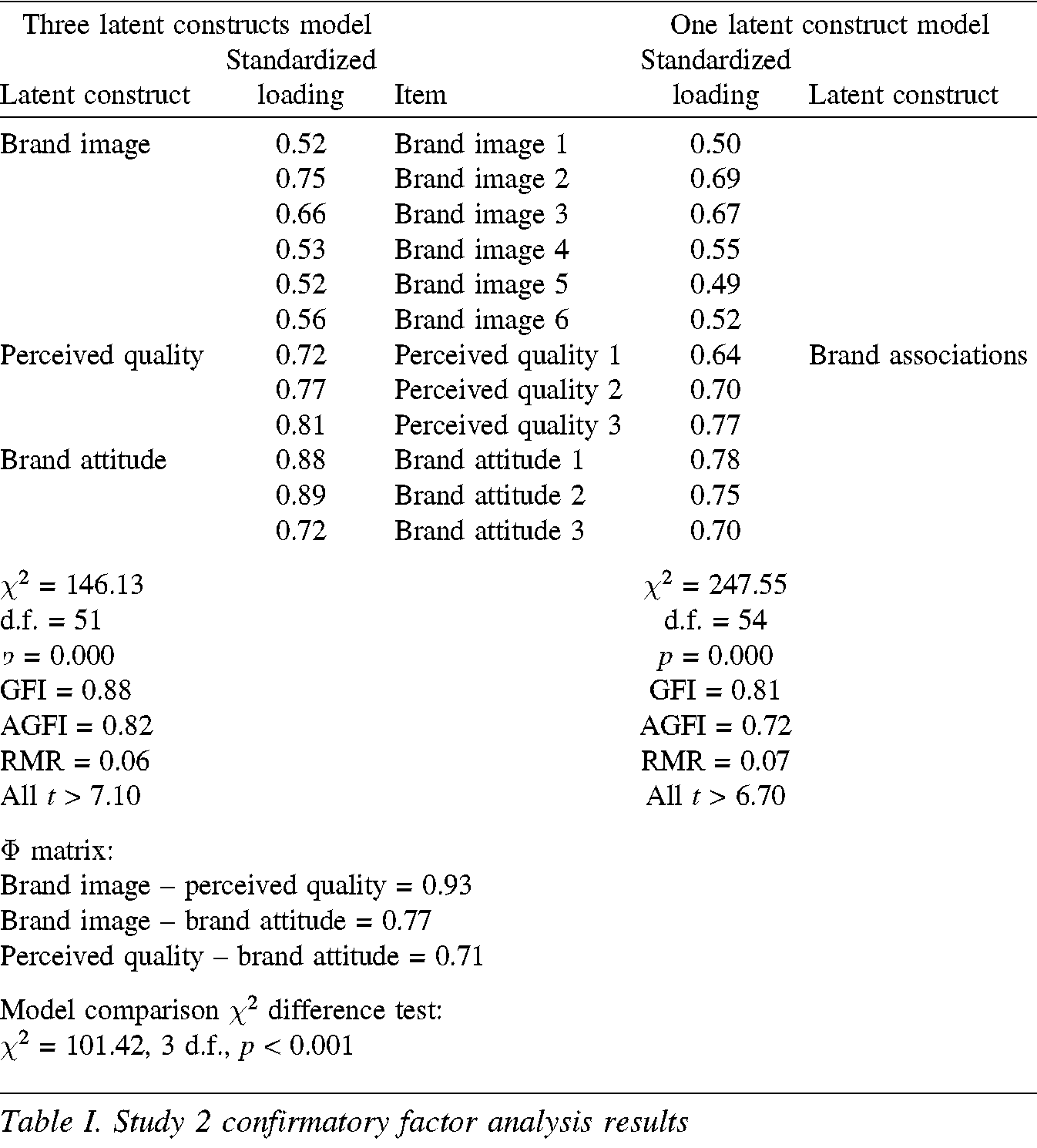

Dimensionality of the scales. The reliability of the three scales was checked using coefficient alpha. The alpha was 0.78 for the six-item brand image scale, 0.77 for the three-item perceived quality scale, and 0.87 for the three-item brand attitude scale (see Appendix for descriptive statistics for the scales). In addition, the dimensionality of the scales was checked by comparing two latent construct confirmatory factor analysis measurement models using LISREL VII. The first model was a three-construct, three-dimensional model, and the second was a one-construct, one-dimensional model. The three-dimensional model fit the data much better, with a GFI of 0.88 compared with 0.81 for the one-dimensional model, and an AGFI of 0.82 for the three-dimensional model compared with 0.72 for the one-dimensional model. As suggested by Sharma (1996), the chi-square statistic for the two models was compared to ascertain whether the three-dimensional model’s fit represented a significant improvement over the one-dimensional model. The chi-squared difference test for the two models was significant (101.42, 3 d.f., p < 0.001). These results appear to indicate that brand image, perceived quality, and brand attitude are distinct constructs which measure different dimensions of brand associations[1]. The complete model results are shown in Table I.

Study 3

Two pre-tests. One objective of Study 3 was to test further the dimensionality of brand associations using a variety of real brands. Another objective was to investigate whether the degree of dimensionality varies depending on a brand’s familiarity. Two pre-tests were used to identify product categories and brands commonly used by an undergraduate student sample, and to develop scale items to measure brand image for each of the eight brands using the same procedure as in studies one and two. Brands were chosen based on the relevance of the product category to students, the availability of actual print advertisements for real brands in those product categories, the brand’s familiarity, and the type of product. An important part of Study 3 was extending the measurement of brand associations to a wide range of brand familiarity and product types (see Bearden and Etzel, 1982). The eight selected brands were Pepsi (soft drink), Grey Poupon (mustard), Timex (watches), Post Honeycomb (cereal), Whirlpool (washing machines), Pepperidge Farm (raisin bread), Taylor Made (golf clubs), and Broderbund (computer game). A total of 100 undergraduate students were shown the eight brand advertisements for 30 seconds each. Different, random sequences were used for each subject to minimize order effects. Following each advertising exposure (prior to seeing the next advertisement), subjects were asked to indicate their level of familiarity with each brand on a seven-point semantic differential scale anchored with “familiar” and “unfamiliar”. The familiarity scale was chosen instead of a dichotomous measure of brand awareness to capture a wider range of possible responses.

Study 3 results

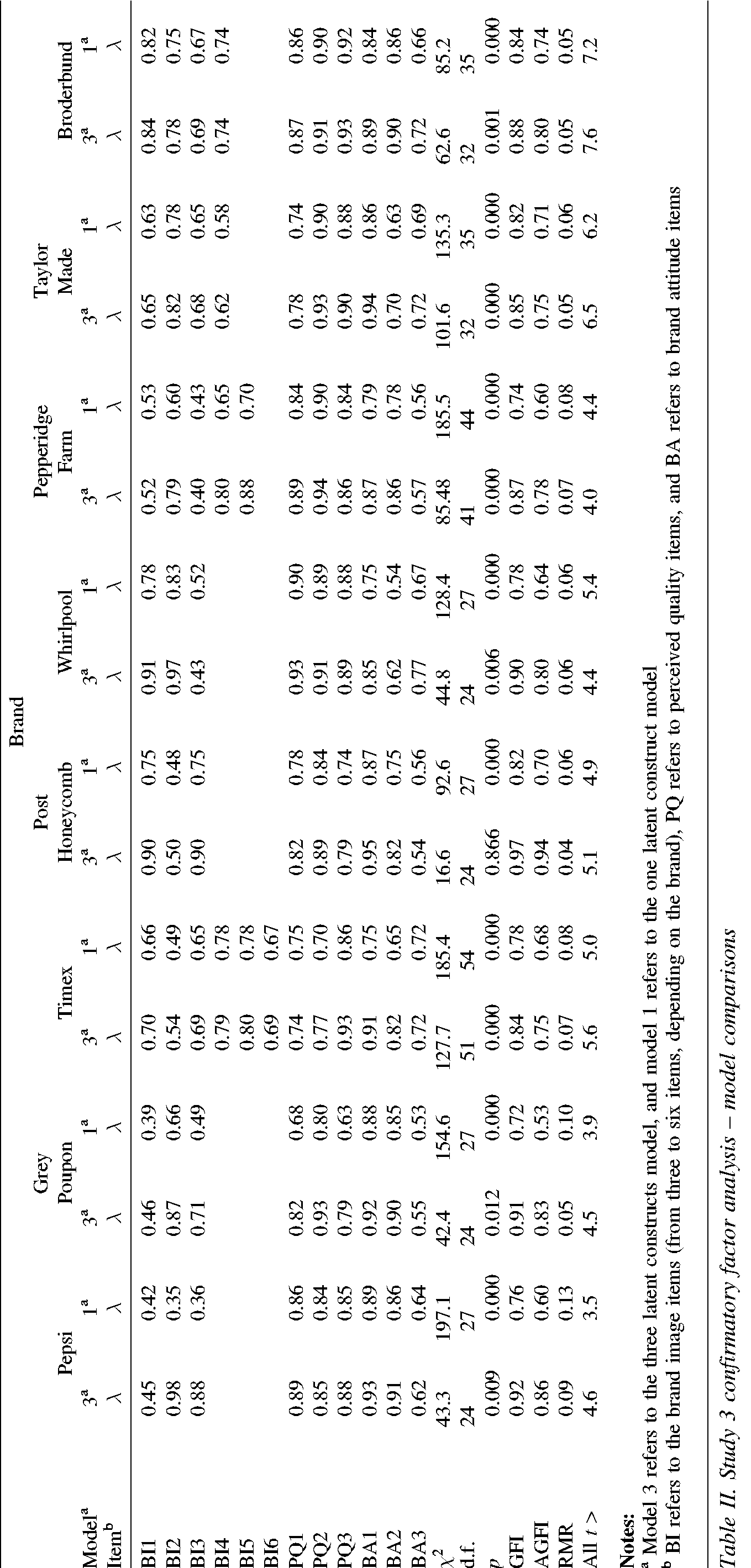

Two confirmatory factor analysis models were compared for each of the eight brands to check for discriminant validity of the measures using LISREL VII (see Sharma, 1996). AGFIs for the three latent construct models range from a low of 0.75 (Taylor Made and Timex) to a high of 0.94 (Post Honeycomb). For all eight pairs of models, the three distinct constructs model fit the data better than the one latent construct model based on chi-squared difference tests. These results are shown in Table AI and TableAIa

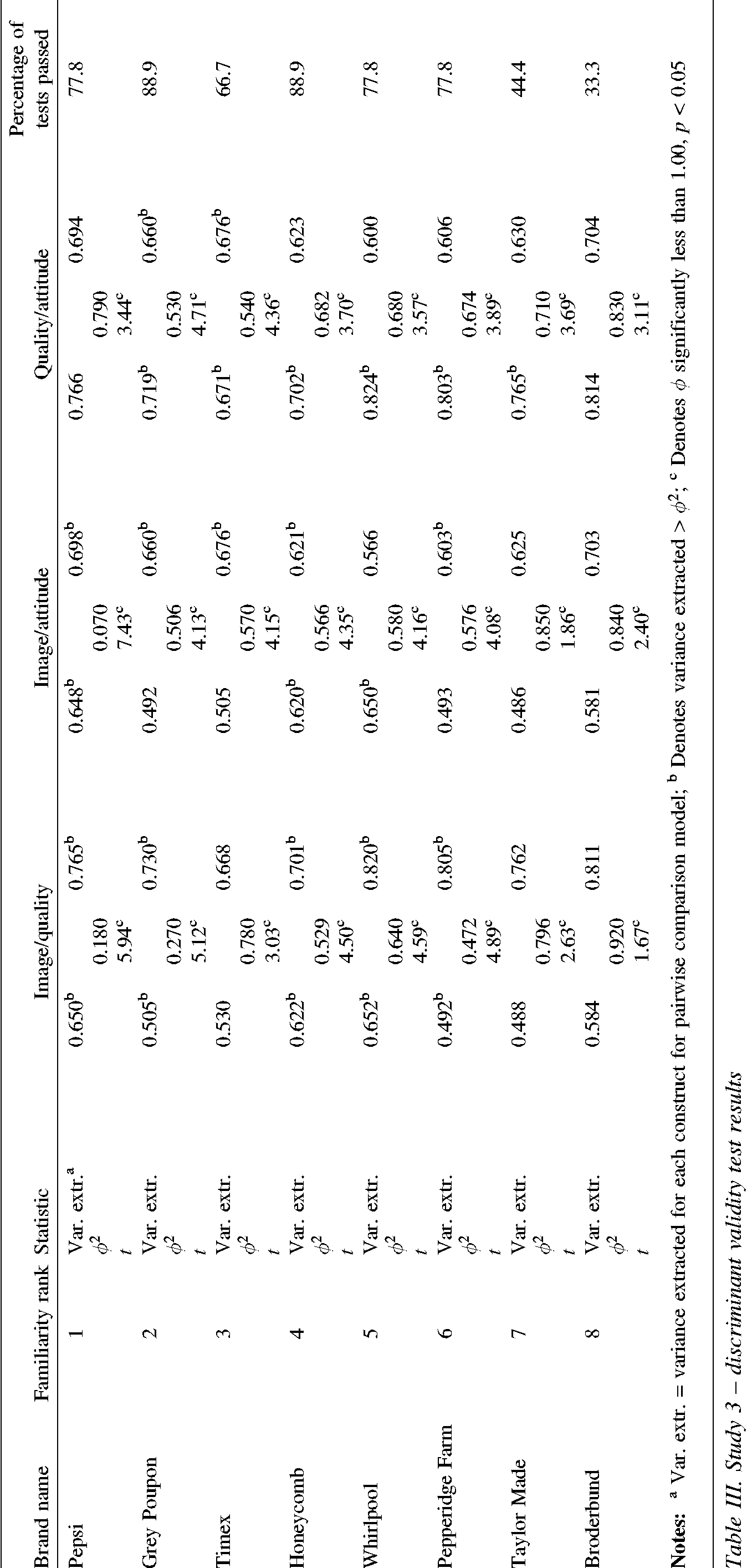

Discriminant validity tests. In addition to the chi-squared difference tests recommended by Sharma (1996), we also conducted additional discriminant validity tests to investigate the differences across each pair of scales for each of the eight brands. The first of these tests was to check the phi coefficient for each pair of constructs in a two latent constructs model (i.e. brand image and brand attitude, brand image and perceived quality, and brand attitude and perceived quality) for each brand included in Study 3. Three comparisons were examined for each of the eight brands, for a total of 24 confirmatory factor analysis models. All 24 phi coefficients are significantly less than 1.00, satisfying the first of the additional discriminant validity tests we performed (Bagozzi and Phillips, 1982). These results appear in Table III and Table IIIa

The second test, suggested by Fornell and Larcker (1981), compares the phi coefficient squared for each of the 24 pairs of constructs with the variance extracted for each latent construct in the same two latent constructs model. If the variance extracted for the individual construct is greater than the phi coefficient squared, it is additional evidence of discriminant validity. None of the brands passed this more stringent test of discriminant validity for all six comparisons (two comparisons for each of the three pairs for each brand), however, Grey Poupon and Honeycomb passed this test for five out of six tests, whereas Broderbund failed this test for all six comparisons. We express the number of paired discriminant validity tests passed for each brand as a percentage in Table III. Grey Poupon was the highest brand in terms of tests passed with 88.9 per cent and Broderbund was the low brand with 33.3 per cent.

To determine the relationship between brand familiarity and the dimensionality of brand associations, a correlation coefficient was calculated using brand familiarity (measured on a seven-point scale) and the percent of discriminant validity tests passed (from Table III) for each brand in Study 3. The correlation coefficient was large, positive, and significant (0.77, p = 0.025). More familiar brands were more likely to satisfy discriminant validity tests for the three constructs in our study.

Separate and distinct dimensions. Study 3 results indicate that brand image, perceived quality, and brand attitude are separate and distinct dimensions of brand associations for a variety of brands and product categories, on an overall level. However, when more stringent tests of discriminant validity are used, looking more closely at similarities across pairs of constructs, differences which depend on the brand’s familiarity, begin to emerge across brands and product categories. In other words, our results indicate that brands such as Grey Poupon and Whirlpool that are more familiar to consumers tend to have more highly structured brand associations in memory. Brands which do not have high familiarity, such as Broderbund, do not have highly-developed brand associations in consumers’ memory, and hence, brand associations for these less-known brands tend to be uni-dimensional.

Discussion

Given the importance of brands for many organizations, and the frustration many firms face in trying to measure brand perceptions such as brand associations, the results of our study offer valuable implications, both for marketing practice and future research.

Managerial implications

Desirable goal. Measuring brand associations is a desirable goal for many firms. Practitioners want a simple protocol for measuring brand associations which can be applied across brands, product categories, and markets (Aaker, 1996b). The lack of a simple, straightforward approach inhibits managers’ abilities to differentiate, position, and extend brands (Aaker, 1996a; Dyson et al., 1996).

It would be convenient if a common brand image scale such as Aaker’s (1997) brand personality scale could be used for all brands in all product categories. Unfortunately, the brand personality construct does not apply to many brands. In fact, researchers have been unable to identify any broad or abstract category of brand attributes such as prestige, personality, or functional performance that are generic. As an alternative, we offer a new protocol to measuring brand associations – those intangible brand assets which consumers hold in memory related to a brand name and symbol – an approach which is simple and yet captures three dimensions of brand associations across product categories. Although we are not able to offer a set of generic scales that can be used across product categories, managers can use the proposed protocol, which consists of developing customized scale items to measure brand image, together with the existing, general scales measuring perceived quality and brand attitude, in regular tracking studies to measure brand associations over time. The challenge is to select scale items that tap into consumers’ unique associations for a particular product category.

Consumer by consumer basis. A more complete measure of brand associations would be on a consumer by consumer basis using a depth interview technique to elicit an unbiased picture of a consumer’s associations for a brand (e.g. Fournier, 1998). Yet such an approach is unwieldy when large national samples are required for quantitative studies. Results of the studies reported here demonstrate that existing measurement techniques from the marketing literature are reliable and valid ways to measure brand associations, and that the three measures combined in this study for the first time measure different dimensions of brand associations for well-known brands.

An interesting conclusion of our study is that well-known brands tend to exhibit multi-dimensional brand associations, consistent with the idea that consumers have more developed memory structures for more familiar brands. This is similar to findings reported by Kirmani et al. (1999), which concluded that consumers perceive prestige brands differently than functional brands in that prestige brands are more closely connected to a consumer’s self-concept (Dolich, 1969). The results of our study extend their conclusions by suggesting that the measurement of brand associations should differ depending on a brand’s familiarity. Consumers may be willing to expend more energy in processing information regarding familiar brands compared to unfamiliar brands. This would be consistent with our finding that well-known brands tend to exhibit more developed brand association structures than unfamiliar brands.

Use of lengthy multiple-item scales. Our results also suggest that it is less important to use lengthy multiple-item scales to measure brand associations for new or relatively unfamiliar brands than it is for well-known brands. Given the multi-dimensional nature of brand associations for well-known mature brands, care should be taken to include at least the three scales identified in this study to tap into the range of brand dimensions typical of familiar brand names.

The protocol developed in our studies can be used to measure brand associations across brands, market segments, product categories, and markets. It can be used to monitor the strength of positioning strategies, to benchmark brand associations for longitudinal study, to examine competitors positioning strategies and to assess the efficacy of current or potential brand extension strategies. It can be used as a major component in a comprehensive brand strength assessment program. We suggest that the best way to begin measuring brand associations is to assess a brand’s attitude and perceived quality. Items tapping brand image can be developed later and added to the measurement process in order to understand all three dimensions of brand associations discussed here.

Limitations and directions for future research

Although an objective of this study was to develop a generalizable protocol to measure brand associations, we restricted our application to consumer goods. Whether this approach would extend to other consumer product categories not included in this study, or to business products, services, or Internet marketing are questions for future study. In services marketing, for example, the company brand is the primary brand whereas in packaged goods marketing the product brand is the primary brand. Consumers buying Prell, Comet, Pampers or Charmin may not know or care that the manufacturer is Procter & Gamble. But with services, customers select or reject the company brand (Avis, H&R Block, or Federal Express (Berry and Parasuraman, 1991). Consumers develop company brand associations rather than product item brand associations. What, if any, are the implications of this difference for brand association measurement?

Impact of new technology. According to an article in Business Week (1998, p. 76), “Net surfers don’t go for emotional product auras and soapy vignettes. The latest theory on Net marketing is ‘rational branding’, and there does seem to be something to it; virtual shoppers want practical benefits”. Aaker has expressed a somewhat different view of the impact of new technology. He believes that, “in the new customized, interactive, integrative world of advertising 10 years from now, brands will be even more important” (Narisetti, 1998). Consumers will have so many choices and be so over-loaded with information that they will rely on strong brands to help them make choices. Strong brands will be those with clear and positive associations. Are brand associations different for Net shoppers than for traditional retail customers? Will they be different in the future?

Do customers in different countries or cultures have different brand associations for specific brands? What are the implications of any differences for brand association measurement and brand management?

Familiarity moderates dimensionality. The research reported here clearly illustrates that brand associations are multi-dimensional, and include brand image, perceived quality and brand attitude. Do these components interact in a meaningful and consistent manner? Are there other dimensions of importance that can be measured in a practical way? For example, Aaker (1997, p. 347) identified five brand personality dimensions and developed a 42-item scale to measure “the set of human characteristics associated with a brand”. Ideally, a subset of these items could be selected to measure the personality dimension of brands that exhibit these characteristics. These findings may also be of value in addressing the conceptualization of consumer perceptions of brands. Familiarity moderates the dimensionality of brand associations.

The use of student subjects inhibits the generalization of these findings to other populations. Our purpose in using students was to have access to a substantial pool of subjects for a number of pre-tests and three main studies, and to develop a measurement method that could then be used for various categories of subjects. We took care to ensure that the products used in our studies were relevant to the test population. Although the specific findings on each brand’s strength may not be the same as the general population’s, we are confident that the measurement protocol is generalizable.

Our measurement approach is also limited since it is based on a traditional paper-and-pencil technique, which may lead respondents to form brand associations that are not already in memory. This simple, practical approach could be complemented with qualitative methods to further investigate the dimensionality of brand associations.

Executive summary and implications for managers and executives

Brand associations a simple construct?

We worry a great deal about our brands. After all, these intangible and confusing things are the heart and soul of marketing. At the same time we wander between seeing brands as precise constructs things we can “micro-manage” and seeing those brands as nebulous, vague images within the minds of our consumers. In truth, and despite the extent of brand research, we remain a long way from have a clear understanding or even a robust description of the brand as a concept.

The problem lies in the fact (something well-recognised by researchers and practitioners alike) that processes within the minds of consumers determine our brand success. In the end, our brand marketing strategies are targeted at the outward manifestations of the consumer’s mindset rather than at that mindset itself. If we ask a person how they think, we never get a wholly accurate response indeed the response is usually what the consumer thinks about what he/she thinks.

Low and Lamb enter into this difficult area of study with the sound view that any measurement to be applicable in the real world needs to be parsimonious. At the same time we cannot fall foul of seeing the brand in terms of single dimensions or concepts. Low and Lamb’s main observation hits the nail on the head they suggest, “… it is difficult to determine if the various constructs they (brand researchers) discuss, such as brand attitudes and perceived quality, are separate dimensions of brand associations … or if they are simply indicators of brand associations”.

As marketers, we have plenty of brand research tools but we are unaware or unclear about the manner in which these tools fit together to provide a picture of the brand in the consumer’s mind.

Image, attitude and quality – are these enough to describe the brand?

Low and Lamb admit that their three measures – combined in one model – do not encompass all the possible dimensions of brand associations. Thus, on one level at least we can suggest that the proposed model has weaknesses. However, Low and Lamb rightly point out the need for a parsimonious set of measures and a degree of clarity about the way in which these measure connect and interact. Image, attitude and perceived quality may not describe a brand in toto but they are three consistent and fundamental elements in brand success.

At the same time, Low and Lamb suggest that the detail of the scales used to measure image, attitude and perceived quality is a matter of significance. We have the ability to use very long and detailed measures or to apply the same parsimony applied to the selection of dimensions to the measurement of those dimensions. Speaking as a practicing marketer, I feel that simpler scales are more applicable. This is not a simple matter of making life easier for the marketer (although that’s very welcome) but also a question of delivering research findings of consistency and clarity.

However there is a further issue – one that Low and Lamb establish through their research. We should take a different approach to the “complexity” of our brand research according to the type of brand. It is said that familiarity breeds contempt but it is also true that familiarity – in this case with a brand – results in a more complex relationship between the consumer and the brand.

Brand type and brand research – the case for different approaches

We can make distinctions according to the extent of the consumer’s familiarity with the brand. We can also consider how brand positioning (e.g. functional or emotional) alters the way in which the consumer develops a relationship with that brand. Low and Lamb argue for the use of more complex research tools in the case of established, image-based brands. And, in contrast, Low and Lamb point out that to use such complex measures for unfamiliar or purely functional brands may be a pointless exercise – consumers simply lack the “brand knowledge” to do justice to a complicated set of scales. The resulting findings could be useless or worse, they could give a false impression about the brand.

However, the case for consistency remains sound. Low and Lamb provide us with the basis for such consistency by proposing a model that can encompass different degrees of scale complexity and different data gathering methods within one model. We can use (as Low and Lamb have done) experimental or qualitative research methods or we can employ traditional quantitative methods. What matters is that we have focused on three important dimensions of brand association. Such an approach is good news at both the tactical and strategic levels of brand marketing. Moreover, in the case of advertising we have the capacity to provide valuable information to creatives and planners.

In the end the decision rests with the brand manager. They have to choose the measures that are applicable to each brand. What Low and Lamb have dome is to pull together three strands in brand research to create a model that is applicable with amendments to scales and data collection to any brand in any situation. However, we must still bear in mind that, while we have as a result, a better understanding of brand associations, there are still important aspects of brand marketing and brand research that fall outside the approach described by Low and Lamb.

Low and Lamb open their paper with the comment that “… marketing researchers have not used a consistent definition or measurement technique to assess consumer perceptions of brands”. We also read how, when suggested definitions or measures are put to use, researchers are unclear as to weather we are dealing with a multi-dimensional or uni-dimensional construct. The proposals that Low and Lamb then validate provide the basis for us to develop better means of investigating consumer brand associations.

(A précis of the article “The measurement and dimensionality of brand associations”. Supplied by Marketing Consultants for MCB University Press.)

Note

- 1. Although the phi correlation for brand image and perceived quality appears to be high (0.93), it is significantly < 1.00, supporting discriminant validity (Bagozzi and Phillips, 1982). The dimensionality was tested using a stricter standard in Study 3, the validation study. The high phi found in Study 2 indicates that fictitious brands’ associations may be less likely to be multi-dimensional since they are based soley on the advertisement given subjects.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| References |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|