Chu-Mei Liu, Associate Professor, in the Department of International Business, Ching Yun University of Technology, Jung-Li, Taiwan, ROC

An executive summary for managers and executive readers can be found at the end of this article.

Introduction

Firms in the corporate world have long recognized the strategic role of brand extension. Many firms capitalize on brand equity through a brand extension strategy. Brand extension involves the use of a brand name established in one product class to enter another product class (Aaker, 1990; Tauber, 1988). For example, Ivory shampoo, Jell-O frozen pudding pops, Bic disposable lighters, and NCR photocopiers are successful extensions of familiar brands to new product categories. Brand extension as a marketing strategy has become even more attractive in today's environment where developing a new product costs a lot of money and can be time consuming.

Literature on extensions dominantly addresses the question of how the parent or core brand helps the new product during its launching stage. Although literature touches on the possible reciprocal effects of the new product launching on the equity of the core brand, their number is limited. This study examines the proposition that brand extensions’ launching performance could affect the equity of the parent brand.

Conceptual framework

Launching of a new product is usually done through brand extensions. The newly introduced brand extension capitalizes on the equity of the already established (core) brand name (DeGraba and Sullivan, 1995; Pitta and Katsanis, 1995) or even the company or corporate name (e.g. San Miguel, Coca-Cola). Consumer familiarity with the existing core brand name aids new product entry into the marketplace and helps the brand extension to capture new market segments quickly (Dawar and Anderson, 1994; Milewicz and Herbig, 1994). This strategy is often seen as beneficial because of the reduced new product introduction marketing research and advertising costs and the increased chance of success due to higher preference derived from the core brand equity. In addition, a brand extension can also produce possible reciprocal effects that enhance the equity of the parent brand. Swaminathan et al.'s (2001) study affirms that the use of a brand extension strategy can result in induced trial due to brand awareness and equity among existing consumers of the parent brand.

From a managerial point of view, extension trial should also strengthen consumers’ propensities toward buying the parent brand unless the extension experience is negative and reduces the parent brand's equity. This effect is most pronounced among consumers who have low levels of loyalty toward, or exposure to, the parent brand. On the other hand, while the possibility of equity reduction exist among highly loyal consumers of the parent brand, its effect slow because of their strong attachment to the parent band resulting from previous positive experiences.

Common brand extension approaches

Brand extension strategy comes in two primary forms: horizontal and vertical. In a horizontal brand extension situation, an existing brand name is applied to a new product introduction in either a related product class or in a product category completely new to the firm (Sheinin and Schmitt, 1994). A vertical brand extension, on the other hand, involves introducing a brand extension in the same product category as the core brand, but at a different price point and quality level (Keller and Aaker, 1992; Sullivan, 1990). There are two possible options in vertical extension. The brand extension is introduced at a lower price and lower quality level than the core brand (step-down) or at a higher price and quality level than the core brand (step-up). In a vertical brand extension situation, a second brand name or descriptor is usually introduced alongside the core brand name in order to demonstrate the link between the brand extension and the core brand name.

Although a brand extension aids in generating consumer acceptance for a new product by linking the new product with a known brand or company name, it also risks diluting the core brand image by depleting or harming the equity which has been built up within the core brand name (Aaker, 1990). In the local setting of the present study, the case of a popular high class restaurant chain using its popular “Coveland” brand name in the introduction of its “tourist car rental” venture is a typical example. The inappropriate brand extension created damaging associations, which may be very difficult for a company to overcome, a situation similar to the findings of Lane and Jacobson (1995) and Reis and Trout (1986).

While the brand extension must capitalize on the core brand, it must create its own niche within the company's brand-mix. In effect, while capitalizing on the equity of the parent, it must at the same time try to break away from the existing “core brand loyalty” and ultimately establish its own brand loyalty (new product). A central influence on current purchase of the core brand is the effect of its previous purchase which can be conceived as the inertial effect of consumers tending to rebuy the brand they purchased previously. Previous purchase is distinct from underlying brand preference. Lattin (1987) and Bucklin and Lattin (1991) captured the dynamic (previous purchase) and static (preference) components of brand “loyalty.” Enduring brand beliefs and attitudes fall under the realm of the label static preference.

When an extension is launched, current advertising is expected to have a positive influence on its current purchase. The theory of hierarchy of effects (Aaker et al., 1992; Aaker and Day, 1974; Lavidge and Steiner, 1961) points to the primary role of advertising as enhancing brand awareness and beliefs and of announcing the existence of the brand or persuading consumers that the brand possesses various attributes. If these efforts are successful, the consumer should be more likely to purchase the brand extension by switching from the core brand to the brand extension. Complimentary purchase could also happen.

Reciprocal effects

Positive reciprocal effects exist only when an average-quality parent brand (in comparison to competitors) introduces a successful extension (Keller and Aaker, 1992). Evaluations of parent brands that are already well regarded will not change significantly as a result of favorable extension experience. Furthermore, enhancement effects exist for brand extensions that are similar to the parent brand (Gurhan-Canli and Maheswaran, 1998). On the other hand, negative reciprocal effects can occur when the extension similarity to the parent brand is extremely low. However, this can also happen when the extension is highly similar to the parent brand, but not obvious.

Likewise, dilution of a family brand name occurs in response to incongruent and negative information about the extension, particularly when the extension is perceived to be similar to the parent brand (Gurhan-Canli and Maheswaran, 1998). Negative reciprocal effects also exist at the brand attribute level (Loken and Roedder-John, 1993) but are not clear at the overall attitude level (Keller and Aaker, 1992).

Usually a new product is tried by a group of consumers who are heterogeneous in their prior experience with the parent brand: prior users, prior shifters, and prior non-users. A successful trial results in a favorable experience and furnishes new information regarding the brand name to both prior users and prior non-users. The learning provided by the product experience will lead to strongly-held beliefs regarding the extended brand (Hoch and Deighton, 1989; Kempf and Smith, 1998). Roedder-John et al. (1998) viewed brand knowledge as a network of beliefs and associations. Hence, the beliefs regarding the extension brand are transferable to the parent brand. Keller and Aaker (1992) and Loken and Roedder-John (1993) posited that two conditions must be present for the transfer to occur:

- The extension information must be deemed relevant to the parent category. This mandates similarity between the parent and the extension categories.

- The beliefs about the parent brand must undergo a change.

Conversely, consumers with low to moderate loyalty toward the parent brand, those who have less exposure to the parent brand, and those that have negative association, particularly the non-users, are more likely to be receptive to change their beliefs and are prone to try the new brand (extension).

If trial results in an unsuccessful brand extension, it is likely that extension triers will get negative or at least neutral information regarding the extension. Among the prior users, the negative results of the extension trial can provide new negative information that can contradict their existing knowledge structures. For non-users, choice of the parent brand is already zero – hence, there is no more effect of the negative information on their current choice.

The notion that advertising might interact positively with experience is rooted in the work of Ehrenberg (1974). There is empirical evidence showing that advertising has a disproportionate effect on those “loyal” to a brand (Raj, 1982). Smith and Swinyard (1983) provided a cognitive foundation differentiating between lower order beliefs, which are held prior to brand usage experience and are hence more tentative, and higher order beliefs, which form after extensive usage and are therefore more resistant to change. According to Smith and Swinyard, advertising could work by two possible advertising-usage interactions. One would occur by advertising helping to establish source credibility. The other would occur by advertising setting up a “predisposition” for a favorable usage experience, and then the favorable experience would determine subsequent purchase behavior.

Deighton (1984, 1986) described advertising as a “frame” on the brand usage experience, either predictive or diagnostic. Framing might occur before (predictive) or after (diagnostic) the actual experience. Before the experience, the advertising might focus the consumer on the brand's best attributes so that when the consumer evaluates the usage experience, the result is more favorable because the consumer evaluated the brand primarily on these criteria. After the experience the advertising could suggest to the consumer how to make sense of what he or she has just experienced, resolving ambiguities and influencing what is retained in memory. In both predictive and diagnostic framing, the key is that advertising interacts with the usage experience to enhance the likelihood of repeat purchasing.

Consumer evaluation of extension

It is generally believed that linking the vertical brand extension with the core brand will be helpful in gaining consumer acceptance for the newly launched brand extension (Broniarczyk and Alba, 1994). However, introducing a vertical brand extension almost always has a negative impact on consumer perceptions of the firm's core brand (Dacin and Smith, 1994). By its very nature, introducing a vertical extension results in a brand extension which exists in the same narrow product category but which differs from its core brand in terms of quality level. This difference in quality level that is perceived between the core brand and the brand extension leads to consumer concerns, questions, or dissonance about the quality level of the core brand. Perceived ambiguity about the quality level of the core brand and the brand extension will inevitably diminish the favorability with which consumers view the core brand. Research indicates that regardless of whether the vertical extension is a step-up or a step-down extension, the impact on the core brand image is negative (Dacin and Smith, 1994).

Categorization theory can be applied to brand families in an attempt to understand the dynamics of core brands and brand extensions (Meyers-Levy and Tybout, 1989; Sujan and Bettman, 1989; Sujan and Dekleva, 1987). One model from categorization theory, the bookkeeping model (Queller and Smith, 2002), suggests that new information about a brand extension introduction causes consumers to update their beliefs about the brand family and the core brand. Since a newly introduced vertical brand extension deviates from the core brand on both the price and quality dimensions, this leads consumers to reassess the core brand image. The conflicting information about quality level results in a loss of image clarity for the core brand, and it dilutes the core brand image. The difference in pricing between the core brand and the vertical extension also signals to the consumer that there is a difference in quality level. Attaching a vertical brand extension to a different price point increases the risk that the quality image of the core brand will be adversely affected (Loken and Roedder-John, 1993; Reis and Trout, 1986). The net result is a less positive consumer evaluation of the core brand, which occurs regardless of the direction (step-up versus step-down) of the brand extension.

Experience with the parent brand provided the biggest influence. This is expected because, since the product is positioned in a different but similar category to the parent brand, it is perceived as an innovation. Innovations typically result from a change to or the elimination of product attributes or features within an existing category. New products are often derived from one or more existing product categories because people use structured imagination. Thus, when developers use their imagination to develop new ideas, the resulting ideas strongly reflect the structure and properties of existing categories (Ward, 1995). It appears, then, that earlier products are often used as design templates for innovations because the existing product is a viable solution to several potential functional and aesthetic goals (Klein, 1987).

Consumers’ ability to understand and represent innovation is structured and/or constrained by their existing category knowledge. The ease with which consumers can transform their existing category structures to accommodate the discrepant information presented by the innovation will largely determine how they perceive the new product.

Mutability explains the transformability of different feature or attributes in a category schema (Sloman et al., 1998). The mutability of a feature depends on the:

- variability of the feature across category members; and

- number of other features in the category that depend on the feature (Love and Sloman, 1995).

Innovation is assessed with respect to some existing product category. The primary base domain is an existing product category most similar to the innovation in terms of the benefits provided. Therefore, if the innovation presents only a minor disruption in the relationships among the attributes in the primary base domain, an expert in the primary base domain is able to construct relation-based mappings between base and the target domains (new product) easily. This makes transfer of significant amount of useful attribute- and relation-based knowledge from base to target.

A novice is unlikely to recognize the relational similarities between the two domains and may be forced to rely on similarities between product attributes presented in the advertisement (or other marketing communication) for constructing mappings.

Novices have fewer attributes and less attribute information stored in their base domains than do experts. If a new product advertises attributes that novices do not already have stored in their existing base domains, they will have difficulty mapping the new target back to their impoverished base domains. This is the rationale behind previous findings that novices’ comprehension of new products is lower than experts and faces higher learning costs in understanding a novel item in an existing category (Alba and Wesley Hutchinson, 1987).

Effects of the marketing mix

Providing attribute elaboration (information) cues for the brand extension has a positive effect on how favorably consumers evaluate the brand extension. In horizontal brand extensions, providing a small amount of information or elaboration about an attribute of the brand extension led to more favorable evaluation of the brand extension (Aaker and Keller, 1990). The findings from that study showed that providing more information about the attributes of the horizontal brand extension effectively offset potentially negative associations. In general, the type of information given in the information cue should be clarifying or explaining some product attribute about which consumers may be uncertain (Boush, 1993). Reducing consumer uncertainty is expected to increase the likelihood of purchase.

Current sales promotion is expected to have a direct and positive effect on brand choice. This result can be explained by the possibility that price and non-price promotions induce a disproportionate number of brand switchers to buy the brand. However, these consumers simply revert back to their normal purchase rate on the next purchase (Neslin and Shoemaker, 1989). This normal purchase rate is lower than for the average consumer who buys the brand without a promotional inducement. As a result, aggregate repeat rates among promotion purchasers are lower that for those purchasing without promotion (Sheomaker and Shoaf, 1977).

Advertising has a special role in this nature of brand extension. Current advertising is expected to have a positive direct effect on current purchase as elucidated by the theory of hierarchy of effects (Aaker et al., 1992). The primary role of advertising in this framework is the enhancement of brand awareness and beliefs, announcing the existence of the brand, or persuading consumers that the brand possesses various attributes. If these efforts are successful, the consumer should be more likely to purchase the brand – either switching to the brand or remaining with the brand (Deighton et al., 1994; Mahajan et al., 1984).

Figure 1 shows the three possible routes or type of relationships that could result from a brand extension. The first route represents the direct influence of the knowledge factor relative to the parent brand that was developed by constant exposure or experience with the brand. Route 2 represents the reciprocal relationship between the parent and the extension brand. Route 3, symbolizes the possible influences exerted on the customers’ choice or decision to repurchase the extension brand.

This article covers the initial findings (Routes 1 and 2) emanating from a successful launching of two extensions of a major competing brand in the health care industry. Route 3 is a possible area of future research.

Methodology

The parent brand and its extensions

Due to difficulty in acquiring permission for the conduct of this study because of its nature among the major industry players, the research was limited to the flagship brand of an entrepreneurial business venture developing health care soap bars using local fruits as it base in a developing country. Launched five years ago, the acceptance of the product (brand) by the consumers is indicated by its current market share in the category (18.3 percent), ranking second among nine competitors in its industry strategic segment and fourth among 15 competing brands in its category.

As part of the company's growth strategy, it launched a product (deodorant spray) in the deodorant market using the same brand name. Three months later, another product (skin soap) by the same company entered the health care soap category positioned as “whitening” skin soap. Advertising highlighting the brands’ main attributes supported launching of the both new products. The company set as target at least 6 percent of the total national category sales after six months from launching as gauge of success. The deodorant spray product got 6.02 percent while the “whitening” soap was able to capture 7.4 percent by cutoff time.

For purposes of this study, the original soap is considered as the parent brand, the deodorant spray is considered the horizontal extension into a different but similar health care category, and the “whitening” soap is considered a vertical extension in the same category but targeting a different customer segment.

Data collection

With the help of a marketing professor, the initial individual panel of respondents was created among his MBA marketing students. Three groups were created, those buying/using only the parent brand, those using other brands, but having at least bought/used the parent brand three times within two months prior to the start of the study, and those who had not used the parent brand at all.

Since the study design calls for at least 200 members per group, the students were requested to recruit participants from among their friends or relatives along the same selection criteria until the quota was filled up. By the time the study time frame started, the pool consisted of 252 loyal users, 237 with low to medium loyalty, and 310 non-users. From the pool 600 final participants were selected randomly, 200 per group.

The respondents were requested to record the number of times they purchase the parent brand, the deodorant and the “whitening” soap during the five-month period of the study. Likewise, they were requested to indicate if at that the time of a particular purchase they have been exposed to some kind of promotional displays, advertising, or any deal promotions.

Results and discussions

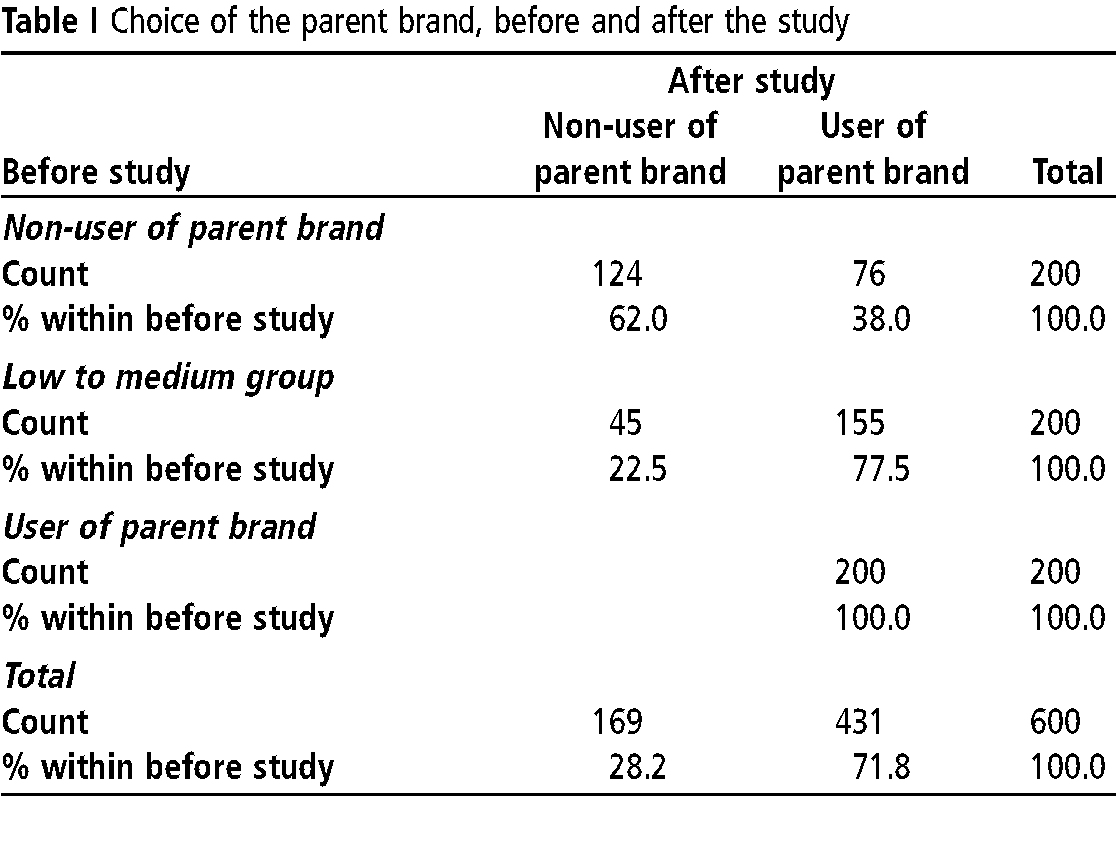

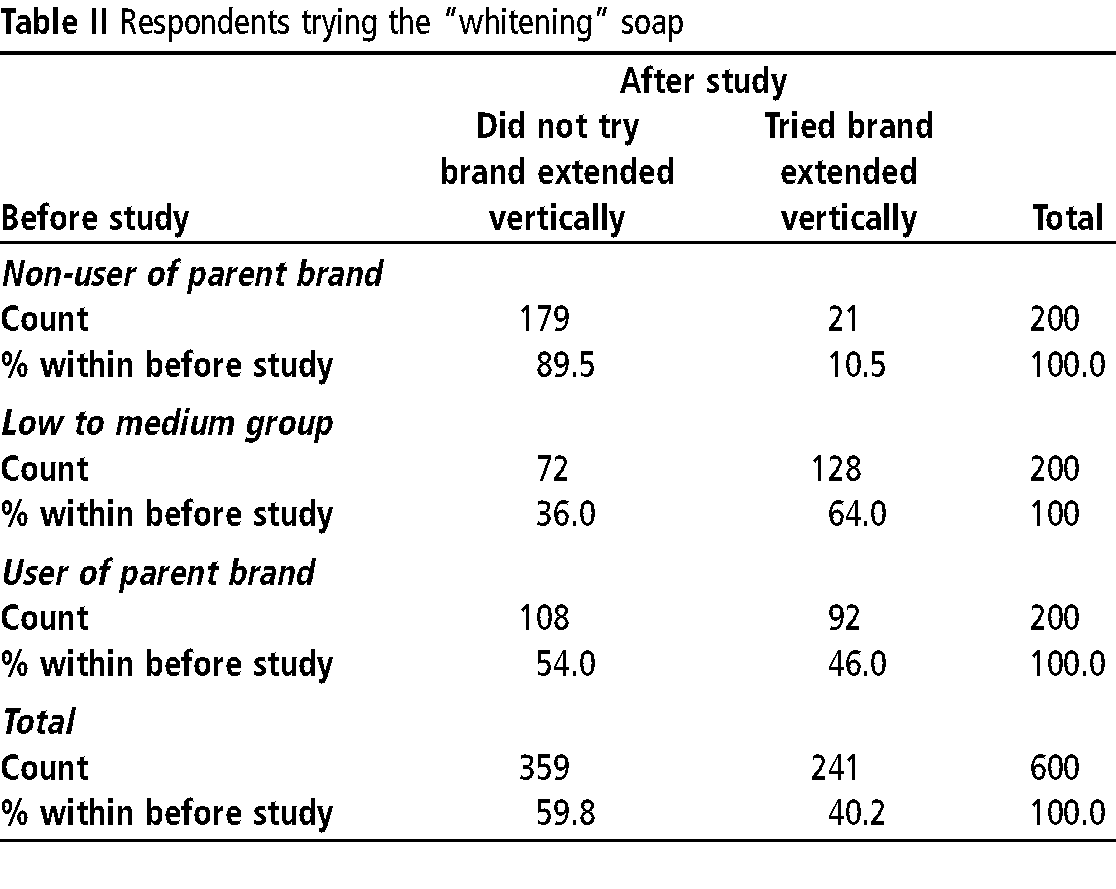

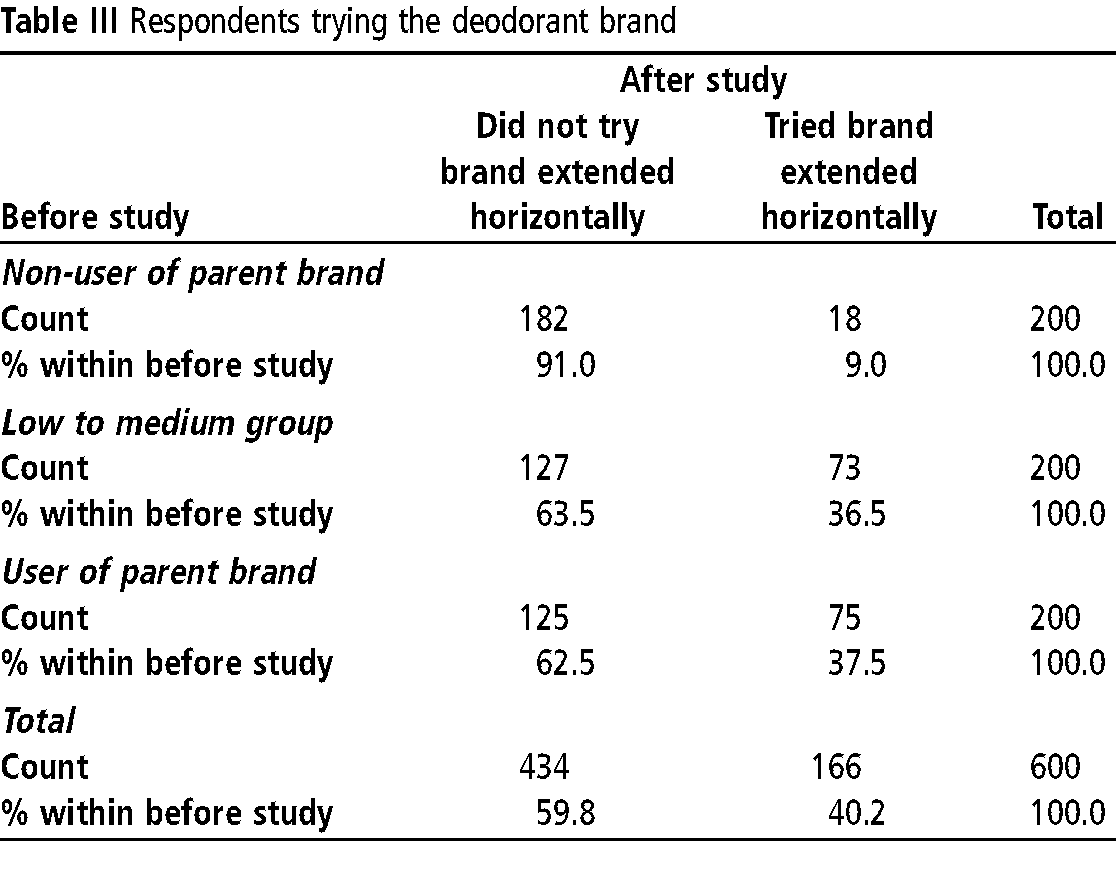

A total of 600 respondents participated in the final generation of the data for the study. To capture the varying degrees of loyalty among the consumers as indicated by literature, the 600 were equally divided into three groups: high loyalty (those buying/using only the parent brand at the start of the study); low to medium loyalty (those using other soaps but having at least bought/used the parent brand within two months prior to the start of the study); and non-user (those who had not used the parent brand at all). During the analysis, however, the respondents with low to medium loyalty were all lump under the category non-users. At the end of the study, 62.0 percent of the non-users became users of the parent brand and 22.5 percent of the low to medium users became loyal user of the parent brand (Table I). Approximately 10.5 percent of the non-users and 64.0 percent of the low to medium group tried the “whitening” soap (Table II), the vertical extension brand. Only 9.0 percent of the non-users and 36.5 percent of the low to medium group tried the deodorant product (Table III), the horizontally extended brand. All those who tried the extension products indicated that they were also buying the parent brand at the end of the study time frame.

Parent brand experience and its repurchase

To serve as a benchmark for the rest of the relationship tests, the initial run of logistics regression had repurchased of the parent brand as its dependent variable, coded 1 if repurchased and 0 is not purchased. Previous experience was operationalized in terms of the relative number of times the product has been purchased during the duration of the study, and exposure to the usual point of purchase displays, advertising and promotional deals served as independent variables. Price was operationalized not in terms of its actual retail level, but as a deviation from the average of the prevailing prices of the competing brand at the time the purchase was made.

Results of the logistics regression show a significant omnibus test of model coefficients (?2 = 696.992), a model's predictive power of 98.5 percent. As could be gleamed from Table IV, the only significant influence on the repurchase of the parent brand was the consumer's experience (3.229). This findings jibe with the points raised by Keller and Aaker (1992) about the “ceiling effect” that the evaluation and ultimate choice of well-regarded brand names generally do not change on account to exposure to routine marketing mix activities.

Route 1: parent brand experience and trial of “whitening” soap – vertical extension

This product is positioned in the same category as the parent brand but projected for a special “need” of the consumers, skin “whitening.” The brand is naturally priced higher than the parent brand.

Results of the logistics regression show a significant omnibus test of model coefficients (?2=162.076), a model's predictive power of 61.8 percent.

Point of purchase displays (1.249), advertising (3.318), and parent brand experience (0.220) significantly contribute to the trial decision for the vertically launched extension brand. The high influence of advertising highlights its role in the transfer of information necessary to enhance the distance between a parent brand and the extension (see Table V).

Distancing techniques are the means through which the brand extension is positioned closer to, or farther away from, the core brand. A variety of linguistic and graphical distancing can be used in advertising, sales promotion, and on packaging. This could be the explanation of the high influence of advertising.

Although the influence of price is not significant in this case, its negative direction is in accordance to the inverse price-demand relationships.

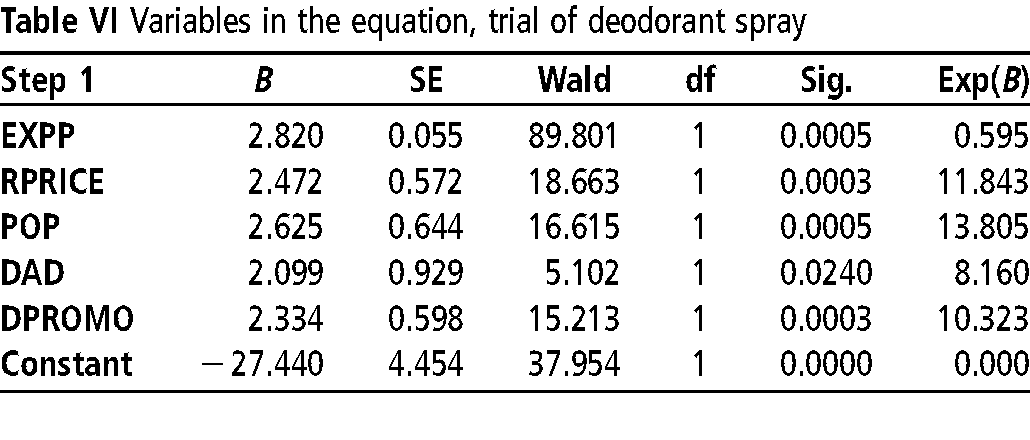

Route 1: parent brand experience and trial of the deodorant brand – horizontal extension

Results of the logistics regression show a significant omnibus test of model coefficients (?2=286.376), a model's predictive power of 77.4 percent. All the independent variables contributed significantly to the trial of the deodorant brand with experience providing the highest effect (2.820). This highlights the role of the parent brand image in the entrance and acceptance of the extension in the new product category. The significant contributions of the elements of the marketing mix only indicate that in entering a new category, one must not depend only on the parent brand's equity (see Table VI).

Route 2: reciprocal effects of brand extension introduction on the parent brand

The influence of the “ceiling effect”, attitudinal shift, and prior usage was capture in the analysis through the inclusion of experience with the parent brand among the independent variables. To test the moderating effect of consumer heterogeneity, choice before extension trial and choice after extension trial were tested (as dependent variables) with the same set of independent variables (experience with the parent brand, reciprocal effect of successful trial, relative price, point of purchase display, advertisement and deal-promotion). Stepwise binary logistics regression was the main statistical tool used.

Vertical extension

With choice before trial as the dependent variable, only experience with the parent brand (3.267) showed significant influence on choice (Table VII, A, Step 1). Since this group of respondents is already exposed for some time, to and with the parent brand, they have become highly loyal users of the brand with high propensities to purchase the brand. As cited by Keller and Aaker (1992) consumers in this type of category generally do not change their choice on account of exposure to favorable extension information.

Another issue that tends to support this finding comes from the fact that the extended brand was positioned in the same category as the parent brand; hence the “expert-novice” characteristics of consumers’ comprehension and perception based on knowledge primary base domain and secondary base domain (Moreau et al., 2001) applies. The vertical extension brand presents only a minor disruption in the relationships among the attributes in the primary base domain. By their experience with the parent brand, the respondents are experts in the primary base domain and are able to construct relation-based mappings between base and the target domains (new product) easily. This makes transfer of significant amount of useful attribute- and relation-based knowledge from base to target and not vice versa.

The above point is further amplified by the results of the analysis when the dependent variable was changed to choice after the extension trial. Trial experience (1.981) with the extension and point of purchase display (5.632) positively and significantly contributed to the choice of the parent brand (Table VII, A, Step 4). As can be noted from Tables I-III, after the trial some respondents from the parent brand non-user group shifted to the parent brand. This shifter groups can be considered as users with zero to medium levels of loyalty, or novice according to the Moreau et al.'s (2001) classification. To the shifters, the exposure to the extension brand induces positive reciprocal effects by enhancing brand familiarity, strengthening brand attitude, which ultimately increased the likelihood of their purchasing the parent brand (Keller and Aaker, 1992).

According to Moreau et al. (2001) a novice is unlikely to recognize the relational similarities between knowledge primary base domain and secondary base domain and may be forced to rely on similarities between product attributes presented in the advertisement (or other marketing communication) for constructing mappings. This supports the significant contribution of the point-of-purchase variable

Horizontal extension

The sequence and independent variables that entered the models amplify the role of product hierarchy development once horizontal extension is implemented (see Table VII, B, Step 3). This is indicated by the influence of experience with the parent brand in both the loyal (3.498) and shifter's groups (1.151) and the support extended by advertising among the shifters (2.627).

The positive reciprocal effect in both the loyal and shifter's group is partly explained by the product hierarchy doctrine in the case of the loyal group. For the shifter's group, the findings are generally consistent with the findings of Gurhan-Canli and Maheswaran (1998) that enhancement effects exist for brand extensions that are similar to the parent brand and Roedder-John et al. (1998) that those who have less exposure to the parent brand are more likely to be receptive to change their beliefs.

Smith and Swinyard (1983) provided a cognitive foundation for the concept of framing by differentiating lower-order beliefs, which are held prior to brand usage experience and are hence more tentative, and higher-order beliefs, which form after extensive usage and are therefore more firm. Advertising could work by two possible advertising-usage interactions. One would occur by advertising helping to establish source credibility. The other would occur be advertising setting up a “predisposition” for a favorable usage experience, and then the favorable experience would determine subsequent purchase behavior. All these issues are given as foundations in the developed or further enhancement of an existing product hierarchy.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that a positive reciprocal effect of extension trial exists, particularly among nonloyal users and among prior nonusers of the parent brand. These positive reciprocal effects also appear to translate into market share increases. Category similarity appears to moderate the existence and magnitude of positive reciprocal effects. There is also an indication that prior parent brand experience acts as a moderator of reciprocal effects. This area, however, must be further studied.

Brand managers need to consider potential reciprocal effects in assessing the benefits of extension introduction. The role of brand extensions in enhancing the appeal of the parent brand among prior nonusers of the parent brand has been overlooked as an important added benefit of the extension strategy.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| References |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Further Reading |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Welcome to the brand family We all have a tendency to adopt a narrow focus in planning and development of strategies. Despite all the encouragement to take a wider view, we inevitably concentrate on the central issues associated with whatever strategy we are involved in developing. In the case of brand extension strategies, this concentration – on the extension rather than on the extension and the parent brand – can result in us missing opportunities that would otherwise be apparent. Brand extension as a strategy is very common. Most new products – whether they are line extensions or entries into new product categories – are launched using established brand with a significant amount of brand equity. The reasons for this are very clear. The existing brand is already familiar to consumers meaning that our promotional focus is on the new product rather than on establishing an entirely new brand. In addition we expect to draw on the market strength of the existing brand and, by using an established set of images, to reduce the time it takes to get the product to market. However, planning for brand extensions focuses either on the brand extension itself or on eliminating the potential negative impact on an established parent brand. We do not pay sufficient attention to the positive impact on the parent brand that might come from an extension. Chen and Liu provide us with some insights that might encourage us to look at the entire “brand family” rather than at individual brand variations within that family. Brand extensions can bring new customers for the parent brand When we launch a new product as a brand extension, we do so in the expectation that existing buyers of the parent brand will try out the extension because of its positive associations. This transfer of brand equity represents one of the strongest reasons for adopting brand extension rather than a new brand. However, we do not consider that by extending the width of the brand, we may attract new users to the parent brand through brand extension. Chen and Liu recognize that non-users of the parent brand may become users of the brand extension. And, by getting positive brand equity from the extension there is a transfer back to the parent brand resulting in those former non-users trying out the parent brand. In planning extensions, therefore, we must consider the parent brand as well as the extension. In doing so we need to recognize the promotional opportunities that flow from the new extension. There is no reason for us not to make the link to parent brand more explicit through sales promotions and direct advertising reference. Since, as we read elsewhere in this issue of The closer the fit, the bigger the reciprocal benefit Having recognized the existence of positive effects on the parent brand from brand extensions, we need to consider the circumstances under which that benefit is biggest. Chen and Liu point out that similarity between categories changes the magnitude of positive reciprocal effects. In essence, the closer the fit between parent and extension brand, the greater chance we have of securing positive sales benefit for the parent brand from the launch of the extension. This should not be seen as an argument for cautious, step-by-step extensions – although this approach will make it easier to secure the greatest benefit to the parent brand. Instead we should consider the way in which consumers perceive fit between parent brand and the extension. Such perception is often focused on factors other than the specific closeness of the two product categories. While Chen and Liu show that category similarity is important, we could speculate from their findings that the issue of fit is our concern rather than the selection of product category. Brands as a family The most important lesson for marketers from Chen and Liu's work – other than the demonstration that positive benefits can accrue to the parent brand from an extension strategy – is that brand extension should not be seen as parasitism but as symbiosis. We need to look at the parent brand plus extensions as a single “brand family” and to plan our brand strategies accordingly. By treating the brand plus extensions as, in effect, one brand, we are able to take fuller advantage of the positive transfers of interest and equity between the various brand family members. We can use the promotional mix to develop closer links between these members and to encourage users of one brand family member to try out other members. We also have to opportunity to test ideas such as promoting brands alongside their extensions thereby reinforcing the strength that comes from the associations between categories and in the consumer's mind.

|