Design/methodology/approach – To understand the precise role of the entrepreneur and to provide answers to five research questions, a qualitative study based on in-depth interviews with mainly middle-sized companies was undertaken. Striking results were obtained from this exploratory research.

Findings – The paper shows the reader what the role of brand management in SMEs is and all the variables that influence it. It also presents a new model for brand development in SMEs, one that highlights the importance of the internal role of brand management in such an organization. An important finding is that passion for the brand throughout the company is a very important factor, initiated by an active role of the entrepreneur him/herself to achieving brand recognition. It does not cost anything and the impact appeared to be significant. Of course creativity is indispensable in this process.

Practical implications – The change that directors of a relatively small company should make is to place brand management in a top position in their daily mind set. Achieving brand recognition starts inside the organization itself.

Originality/value – For the first time in history extensive research in brand management in SMEs has been combined with the creation of various new theories, resulting in many practical recommendations. These are recommendations that can be used by the reader in his or her own organization.

Introduction

Brand management is a relatively young field of study, and one in which real interest was shown only during the final decade of the previous century. This was also the time when the most important theories were formulated and the most valuable literature produced.

What is striking, though, is that attention was focused only on big companies and multinationals. So it was only on big companies and multinationals that the theories were based and about which the articles were written. Open practically any management book at random and it is a good bet that you will find Coca Cola, Nike, Philips, Unilever, Shell or Procter & Gamble used as the practical examples.

This totally ignores the fact that at least 95 percent of all businesses belong to the small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) group (Storey, 1994), just as it also ignores the fact that in the USA, small businesses have taken the lead from the big ones (Thurik et al., 2003). This is something scarcely mentioned in business literature. In fact, when brand management is discussed in books and journals, SMEs are never mentioned as a separate entity, even though there is a distinct difference in having 10 million, as opposed to 100,000, to invest in your brand, and in having a marketing department of 25 at your disposal as opposed to having to plan and execute marketing campaigns all by yourself.

Nevertheless, everyone knows the stories about a relatively small business that knew how to build a well-known brand. The question is, how long does such a business remain a “small business”? Microsoft, Philips and Nike all started small and, thanks to enthusiastic entrepreneurs, grew into worldwide brands. The founder of Nike, Phil Knight, started working in his spare time in his garage and had to stretch every cent he owned as far as it would go.

So how, as the owner of an SME, do you go about managing your brand? What role does brand management play in such businesses? What problems do SMEs encounter in managing their brands? How do you go about increasing brand awareness? What is the relationship between brand management and marketing? These are all questions that remain unanswered in current brand literature. It is high time, therefore, for a closer study.

Objective

The objective of such a study is twofold. On the one hand, it is to construct a new theory that will contribute to existing knowledge in the field. On the other, it is to provide practical tips to entrepreneurs with an interest in such material. What do they, as the owner of an SME, need to do to build a (strong) brand?

To meet these objectives, a qualitative analysis of a group of middle-sized companies producing consumer goods was undertaken. The study was divided into a quintet of questions and undertakings, namely:

- What role does brand management play in SMEs?

- What are SMEs doing to create a heightened brand awareness?

- Are the problems encountered by SMEs in managing a brand comparable to the problems – recognized by the business literature – they encounter in marketing?

- To test Keller's model in practice.

- To develop a new model from the outcome of the previous four questions and undertakings.

Literature

As has already been stated, practically nothing has been published about “brand management in SMEs”. However, much has been written about “brand management” and about “SMEs”. Much has also been written about “marketing in SMEs”, a subject that it is reasonable to suppose has close ties to brand management.

Definition of the SME

Before proceeding any further, however, a definition of the SME is required. The Bolton Report (Bolton, 1971) was the first to formulate a clear and generally accepted definition of small businesses. Wynarcyk et al. (1993) and Storey (1994) offered a critique of this, although there is little need to spend much time on it. It is more practical to make use of the most recent definition (to be introduced in 2005) from an independent and widely recognized source: the European Union (see Table I).

Now that we have determined to which businesses “SME” refers, the next step is to look at how these companies view their marketing function. A study by Cohen and Stretch (1989) revealed that the most commonly cited problems from the owners of small companies were marketing problems. This agreed with the findings of Kraft and Goodell (1989), who concluded that of the problems most commonly cited by small businesses, 75 percent were marketing-related. Finally, Huang and Brown (1999) provided further confirmation with a study of 973 small businesses in Western Australia.

Marketing is seen, thus, as a troublesome and problematic undertaking for SMEs. But such problems do not appear without reason. They can, in fact, be traced back to a number of well-documented – in the business literature – SME characteristics. Carson et al. (1995) cited the strong focus on product and price. Hill's (2001) study of key factors for effective marketing, confirms that the SMEs' vigorous sales orientation largely determines the character of their marketing. As a result, promotion is pushed to sidelines and the building of a strong brand becomes even more difficult.

The marketing advantages of SMEs

Despite all this, it is possible to recognize several advantages and positive aspects typical of SME businesses in the execution of their marketing. Studies by Carson et al. (1995), Gillinsky et al. (2001), Hill (2001) and Reijnders and Verstappen (2003) all point out that flexibility, speed of reaction and the eye for (market) opportunities constitute, where marketing is concerned, the SMEs' strong points.

Brand management

There are many definitions of brand management. Those of Keller (1998) and Kapferer (1995) share several similarities and describe it in easy to understand wording: A company/establishment that has embedded brand management within its organization recognizes that the implementation of a brand strategy and the management of a brand are not once-only exercises, but a daily recurring aspect of its marketing policy.

The two pillars on which a marketing strategy is based are:

- differentiation: the distinctiveness of a product from that of its competition; and

- added value: a branded article has more value for the customer than an un-branded one.

Aaker's (1996) ten guidelines for the creation of a strong brand are generally accepted within the field of business writing, although none of them apply specifically to SMEs. Keller (1998) is the only author to have paid particular attention to this question. He devotes, it must be said, only three of the 700 pages of his book to this subject but it is at least a beginning. He offers the following guidelines for the building of a strong brand by SMEs:

- Concentrate on building one (or two) strong brands.

- Focus a creatively-developed marketing program on one or two important brand associations, to serve as the source of “brand equity”.

- Use a well-integrated mix of brand elements that support both brand awareness and brand image.

- Design a “push” campaign that aims to build the brand, and a creative “pull” campaign that will attract attention.

- Broaden the brand with as many secondary associations as possible.

Methodology

To understand the precise role of the entrepreneur and to provide answers to the five questions/undertakings listed earlier, a qualitative study based on in-depth interviews with ten mainly middle-sized companies was undertaken. Striking results were obtained.

Typical of SMEs is the often all-controlling and all-deciding role of the owner (director) of the company. And when the role of brand management in SMEs is examined, then it is highly probable that the same owner will take the lead in setting guidelines and making decisions for that as well. Therefore, to guarantee the highest degree of reliability from such a study, it is from this person that the required information needs to be obtained, according to Gilmore and Coviello (1999). And in that, the study eventually succeeded.

It is unlikely that, had conventional quantitative investigation methods been used, the investigation would have attained the desired level of insight into the world of SMEs.

Interviews

Given the fact that barely any literature was available, and that an exploratory study was to be undertaken, the mono-method of qualitative investigation was chosen. The other investigatory methods (participatory observation and the gathering of documentation) were not felt to be applicable.

With the help of loosely structured lists of questions, an attempt was made to conduct the personal interviews in as free a manner as possible, to allow the interviewees sufficient space in which to offer as broad an answer as possible, discussing backgrounds to issues and offering clarification of points raised. This made the context clearer and that, in turn positively influenced the reliability of the results. (Gilmore and Coviello, 1999).

Especially middle-sized companies

The entire organization of the investigation, as well as the list of questions compiled, was overseen by several experts in this field in order to ensure as high a level of validity – both internally and externally – as possible.

The list of questions was tested in advance and, after appointments were made by telephone, discussed in person with those to be interviewed.

The companies studied are, in the main, middle-sized companies with a turnover of between 3 and 29 million and with anywhere from 42 to 170 employees. All the companies produce – mainly on their own premises, all of which are situated in the east of The Netherlands – items for the consumer market. Owing to the breadth of sectors covered by the companies, the results of the study are widely applicable to, and the conclusions it reaches have considerable validity for, companies in other fields of endeavor.

No service industries or non-profit organizations were studied. It is, therefore, open to debate how much relevance the outcome of this study will have to such organizations.

The group of companies studied contained one small-sized company and one micro-company. Both are determined to make their mark on the consumer market. Despite this, however, the findings of this study cannot reliably be projected onto all small-sized and micro-companies but should, instead, be focused on the aforementioned middle-sized companies.

Bonuses of the study

The great bonus of the study lies in the fact that, until now, it was the marketing function of SMEs was that was investigated, as a result of which brand management received scarcely any attention. This exploratory study has, therefore, provided the foundation for further investigations.

Results and conclusions

The results of the study, together with the conclusions arising from it, are arranged in order of the questions/undertakings listed at the beginning of this article. This has been done to ensure maximum clarity and readability.

What role does brand management play in SMEs?

- Just over half of the companies studied admitted that they “do something about brand management”. This answer may be due to the fact that brand management is not clearly understood. But, after the question was clarified, three of the companies questioned still answered that brand management had no part in their daily or weekly operations. Brand management can be said, therefore, to be far from a high priority issue.

- The responsibility for brand management lies, in all cases, at the highest (management) level! Brand policy, changes to the logo and attention given to the brand are matters always decided by the director/owner. Only one or two companies could boast the “luxury” of a marketing manager, to whom the responsibility for brand management could be delegated; yet that did not happen. Other than the director/owner, nobody within the organization was specifically concerned with brand management, nor was it widely discussed or communicated. The fact that eight of the ten people questioned replied that their managerial responsibility for brand management within the company was large effectively confirms this.

- It is notable that in half the companies studied, it is the character of the entrepreneur that is important to the acquisition of a recognized name. Almost all the companies proposed PR as the preferred communications medium for delivering their (brand) message and, in fulfilling that PR function, it was usually the entrepreneur who played a big role. The link between tight budgets and the free publicity-aspect of PR is easily made and extensively used.

- In many cases, the company name is often not the brand name! In only half the companies were both the same, and the study revealed that this was a conscious choice. In most cases, companies made use of one to two brand names.

- For most companies, the idea of co-branding or cooperation with other businesses remains unexplored territory. Only a few made use of a third brand name to create a brand synergy.

- The characteristics that distinguish the brand are not the same as the characteristics that distinguish the product and/or the company. It would be reasonable to expect that there would be more of a connection between the two but, apparently, companies either do not share this opinion or do not even bother to consider it.

Conclusion

In many SME companies, brand management receives little or no attention in the daily run of affairs. Although the owners or directors are the ones to take the lead in this area, they either seldom have the time for it or are not even aware of “brand management” as a concept. And because this concept is not ingrained within such an SME, there are no other employees available to give it sufficient attention.

The entrepreneur, as a person, can be extremely important in building and acquiring recognition for a brand. But while this is recognized, the position of entrepreneur, and the possibilities available to him, are hardly used.

Little consideration is given to the possibilities offered by a (strong) brand, or to the conditions that must be met to create a strong brand. Co-branding – working with other companies to boost the value of a brand – receives no attention at all. And the fact that the company name is often not the same as the brand name further reduces its chances of gaining people's attention.

In short, brand management is not given the priority it needs for a strong brand image to be constructed. And in this the role of the entrepreneur is all-important, both internally and externally.

What are SMEs doing to create a heightened brand awareness?

- It would be reasonable to suppose that, in general, every company aspires to a high recognition of its brand. However, only a few companies stated – without being asked – that high brand recognition was one of the most important goals they wanted to reach with their marketing budget. Yet when the interviewees were asked – directly – whether brand recognition was one of marketing's key goals, the majority answered yes. Thus it can be concluded that, in general, people unconsciously want create a well-known brand.

- Although SMEs place their brand name on as many communications media as possible, from business cards and building facades to packaging and trucks, it is striking that not every company places its brand name on the actual product! Some companies are selling products to consumers who will not be able to see who manufactured or supplied them. Remarkable! Especially because the products were already expensive enough.

- The internet has completely penetrated the SMEs. Every company studied makes use of it.

- The most commonly used media for advertising are word-of-mouth, newspaper advertisements, brochures and PR exercises. Noticeably, less than half the companies studied use the television (either for adverts or sponsoring televised events) to communicate their brand name. This is not something you would immediately expect from middle-sized companies. These are also the same companies that have the results of such activities professionally analyzed.

- The companies readily admitted that they would like their products to project an attractive, chic image. Whether the consumer sees them that way is another question. In addition, the companies would like their brand to be considered a likeable one. Finally, perceived quality plays a key role. Almost half the companies studied hope for such an association. This was also notable when the companies discussed ways of distinguishing their products from those of their competitors. The owners are proud of their products and make a point of letting that be known, but they would also like the consumer to recognize it.

- When all is said and done, it would be difficult to distil, from this study, one common denominator of the skills available within a company that could be deemed necessary for the creation of increased brand awareness. The most commonly proposed term was creativity. A wide range of other factors was mentioned, but only once.

Conclusion

The creation of high(er) brand awareness is not often a conscious goal when determining a company's marketing budget. Only when questioned more closely is it clear that this is a target companies want to attain. But because, for SMEs, generating turnover is just as important a goal, in the short term a company's attention is clearly directed towards sales, and to stimulating them as much as possible, simply in order to survive.

Companies place, naturally, the brand name on as many surfaces as possible, for example, the packaging, the building facades and the company stationery. But the logical next step of placing the brand name on the product itself does not always occur to them. It would appear that such a step is, even for the entrepreneur, less than self-evident.

Within the broad range of communications media, it is striking that most emphasis is placed on television exposure: commercials and sponsorship of televised events. This calls for inventiveness and creativity, with which, for a relatively limited budget, it is possible to gain national recognition.

Entrepreneurs are proud of their products. This reveals itself not just in their wish for the brand to be seen as a signifier of “quality” but also as possessing an “attractive, chic and distinguished design”.

It is difficult to name one single success factor that a company should possess if it wants to create a high(er) brand awareness. What is clear, however, is that creativity is a not unimportant factor. What emerges from the study is that such creativity must first and foremost come from the owner; it should not be expected to emerge from within the company. However, such an attitude has often been created by the entrepreneur him/herself, as shown in the previous paragraph.

Marketing and brand management within SMEs

- The first conclusion to be drawn is that, according to the business literature, the problems commonly attributed to management appear, in practice, to arise from other areas. For example, 75 percent of problems attributed to management would normally be blamed on marketing. But this was definitely not confirmed by the study, which found that purchasing caused the most problems, followed by production and sales.

- But closer examination of the specific problems faced in practice by the marketing function matched the conclusions of the business literature. Of these, capacity (personnel) and budgets were the most frequently cited. A direct link also emerged between such problems and the very nature of SME businesses.

- The practice also agreed with the business literature's observations about the marketing advantages available to SMEs: speed of decisions, short lines and flexibility were considered to be the biggest. One new aspect came to the fore: the awarding of contracts. It was mentioned several times that contracts were awarded to companies because they were small.

- The literature has little to say about the size of SME marketing budgets. This study concluded that a relatively large amount of money is available for marketing. In concrete terms, this frequently amounts to a few hundred thousand Euros or, as a percentage of the funds available to a company, an average of 2.3 percent of the turnover of a company. The majority of companies base their budget plans on a series of scheduled activities, but also make allowance for ad-hoc decisions.

- The SME is obsessed with brochures and folders! Almost every company studied spent a large percentage of their marketing budget on this one area. Other favorite investments include magazine advertisements and in-store display materials. This is obviously an area in which the product-oriented nature of SMEs comes to the fore.

- The ultimate goal that companies seek to attain with such marketing materials is name recognition and (growth in) turnover. What can be called “ordinary” sales! Half of the companies studied operate a “push and pull” strategy.

- The brand management problems observed by the study are hardly comparable with the marketing problems noted in the business literature. The study revealed an abundance of brand-related problems, of which - in three out of the ten companies studied – an insufficient budget was cited as the biggest. This was the one problem shared in common with marketing but it was not, due to the few times it was cited, readily obvious.

The problems observed within brand management are extremely diverse and differ from one company to another. They are, thus, extremely business-dependent.

Conclusion

Little study has been made of brand management within SMEs. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that there is little or nothing to be found on this subject in the business literature.

This is in contrast to marketing within SMEs, about which a relatively large amount is known and has been published. It would simplify both understanding and interpretation if these two closely-related business areas could be brought under one umbrella, especially with regard to similar problems that owners encounter in both areas.

This appears, however, not to be possible. The problems encountered in brand management are rarely comparable to the SMEs' marketing problems described in business literature. They are also extremely diverse and, in the practice, totally different to those described in marketing theory.

The noticeably high marketing budgets that were observed can, perhaps, be explained with two small observations:

- The companies studied are middle-sized. They are not the little corner shop. So some degree of scale is relevant here.

- All the companies studied operate in the consumer market. To reach the consumer, they will usually need a higher budget than they would in a business-to-business situation.

To test Keller's model in practice

The value of three of the five guidelines proposed by Keller for the creation of a strong brand SME were confirmed by this study; those interviewed stated that they were definitely of relevance to their business. Two guidelines, however, were not so readily accepted. On a scale of 1-10, they were given only a 6. In their place, three new guidelines could be added to the model. All were frequently cited by the companies studied as having extreme relevance to their operations.

These changes led to the creation of the following new model.

Guidelines for the creation of a strong SME brand (Krake)

- Concentrate on building one (or two) strong brands.

- Focus a creatively-developed marketing program on one or two important brand associations, to serve as the source of “brand equity”.

- Use a well-integrated mix of brand elements that fully support both brand awareness and brand image.

- Be logical in your policy and consistent in your communications.

- Ensure that there is a clear link between the character of the entrepreneur and that of the brand.

- Cultivate a passion for the brand within the company.

- Design a brand-building “push” campaign and a creative “pull” campaign to attract attention.

- Broaden the brand with as many secondary associations as possible.

It is easy to understand the reasons for the two guidelines being discarded; they simply do not come within the scope of most SMEs' concerns, a fact underscored by the observation that of the companies studied, only a few cooperate with other companies or engage in co-branding.

Clarification of the new guidelines

Re: 4). It is said that a person should be consistent in their policy and their activities. Do not turn left one day then right the next. “Repetition” is the magic word.

With regard to consistency in communications, someone once notably observed: “It's only when you can no longer see the message because you've worked with it so long, so often and so intensively, that it begins to register with your target audience.”

Re: 5). The study showed clearly how great the role of the entrepreneur is to the creation of brand recognition: as a source of inspiration and organization within the company but, principally, as the personification of the brand.

As entrepreneur, you are the brand and you should embody it in everything you do to deliver the message as clearly as is possible. Because it is so real and authentic, not even a multinational's multi-million dollar campaign can deliver as much impact or conviction.

Re: 6). The passion that entrepreneurs express when they talk about their brand must be transmitted to the rest of the organization. Because such businesses are not big to begin with, this can be done. And when this happens, the whole organization should radiate with an enthusiasm for the brand in everything it does. A small, passionate group of people can bring enormous power to bear on the building of a strong brand. So much so that if you were to wake them up in the middle of the night, the first words out of not just the product or brand manager's mouth but also that of the telephonist and storekeeper would be about the brand.

Conclusion

Keller's model is one of the few theoretical publications about brand management in SMEs. Yet how he decided on his proposed five guidelines is unclear. He may have based them on an earlier study, or he may simply have applied sound business reasoning to the matter.

If the latter is the case, that does not invalidate the conclusions even if, later, not every guideline was proved to work in practice.

Ultimately, it was possible to add a trio of new guidelines. Whether these carry more weight than the five proposed by Keller must be determined by further study. It should be stated that, in the opinion of the author of this study, this is indeed the case.

To develop a new model

The “funnel” model for the role of management in SMEs

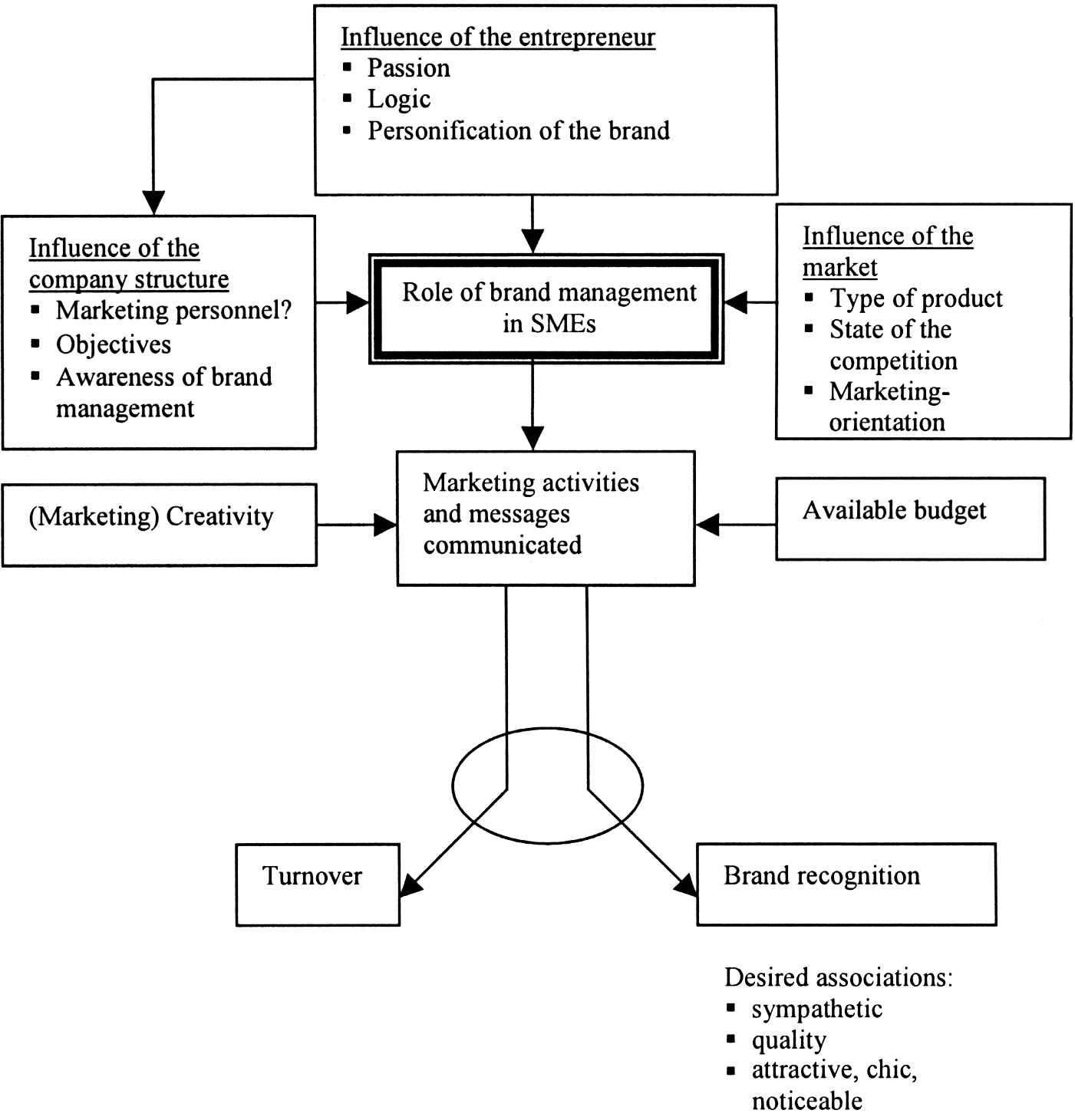

When all the results, as well as the subsequent conclusions, of the study are brought together, a combination of factors becomes apparent. These factors can be represented schematically by the “funnel” model shown in Figure 1.

The owner plays an important double role here. On the one hand he/she determines, as director and manager, the structure of his organization and how much attention it can give to brand management. For example, he/she can do this by appointing a marketing manager or, at the very least, by making the tasks the clear responsibility of a specific employee. But he/she can also accomplish this by setting clear objectives and making the organization aware of the importance of brand management. On the other hand, as the entrepreneur, he/she is often the personification of the brand and, as such, plays a direct role in communicating the brand to the outside world.

Such a scenario (described in the previous paragraph) is more readily noticeable in SMEs than in large companies. First, the influence of an entrepreneur on a business is greater and much more direct in an SME. Second, the brand is much more closely integrated with the entrepreneur in an SME. An attack on the brand is often seen as an attack on him because he is (often) the brand. And that can be both positive, as well as negative, for the company.

Following on from this, the company structure has more influence on the role of brand management in SMEs than it does in large companies. In SMEs, the central question is whether any attention at all is paid to brand management and how, if it is, it is built into the company. In most large companies, the central question is how much attention is there? How many people are in the Marketing department? How many brands does each brand manager manage? How many million Euros can be invested in brand recognition?

The market in which the SME operates also exerts an influence on the role of brand management within the company. The clothing market can be taken as an example: a brand there carries far more weight with a purchase than it does, for example, with the purchase of a radiator. The type of market also determines the role brand management takes within an SME. As well does the type of products a company makes and its market orientation. Finally, the number of competitors, not to mention their size, plays an important role with regard to the SME itself.

The difference with a large company has to do with the fact that an SME is much more dependent on, and guided by, the market but can bring little influence to bear on it; whereas a multinational can exert its will far more and can, if it wants to, change it or even create a (sub)market.

Both groups also exhibit distinguishing characteristics that directly affect the messages they communicate. An SME has, in absolute terms, a much more limited budget than a large company. And a couple of hundred thousand Euros does not go far if you want to build a strong brand. The budget also influences the desired level of creativity available to the marketing. How inventive can a company with relatively little money be in reaching its desired goals and communicating its message effectively?

One last aspect of the funnel model worth noting is that, for an SME, the desired goal of its marketing activities and communications is two-fold. As the study revealed, people want to create brand recognition. But they also want to generate turnover. Which means that they have to concentrate on selling!

Further study would reveal whether, based on its marketing activities and advertisements, its commercials and free publicity, a large company is also so bound to its selling ethos; or whether its foremost goal is the building of a brand and the generation of brand recognition, which is the more instinctive choice.

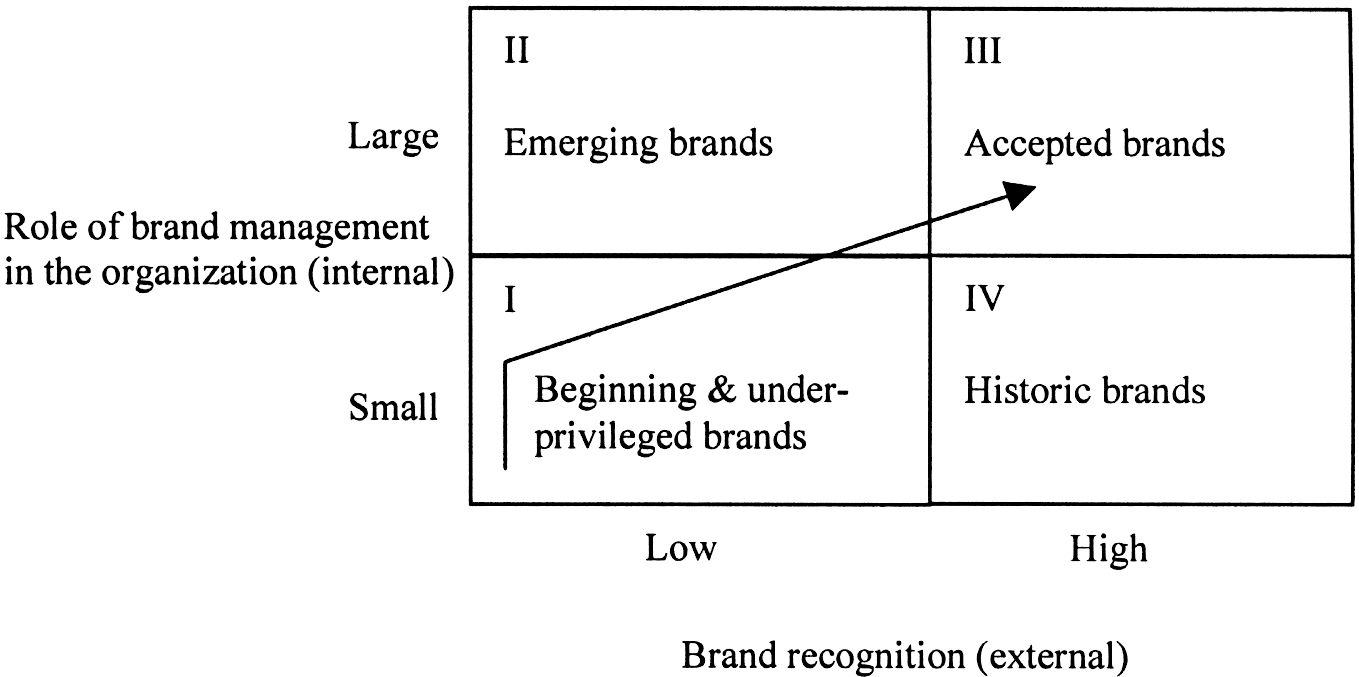

Brand development model for the SME

It is obvious from the study that the role of brand management varies considerably in different companies. In one company it will not be an issue at all; in another, the whole organization will be geared towards it. There is, thus, considerable variety in the internal position of brand management.

Furthermore, what was also striking was that there exist companies with no recognition that are working hard and gearing their whole organization to gaining that recognition. At the same time, the study also found that there are companies that had created a high level of brand recognition but with little conscious effort.

Two axes are plotted on the graph in Figure 2. The vertical axis represents the role of brand management within the organization, measured against the (external) recognition of the brand on the horizontal. The relationship of all these factors forms a new theory of brand management in SMEs: “the brand development model”.

The following observation is appropriate here: there are no objective criteria for measuring the recognition of a brand in SMEs and absolutely none for measuring them in relation to each other. Within SMEs, little research is undertaken into the effects of marketing spend and concepts such as spontaneous or aided brand recognition are well known but never measured. The entries on the horizontal axis are, therefore, subjective. Further research could offer a more objective method.

This is less so on the vertical axis. The previous model (Figure 1) clarifies the role of brand management in the SMEs and shows that the structure of the company, and the position of brand management therein, is a variable that influences the eventual “total role”.

To determine the internal role, the (embedded) position of brand management within the organisation needs to be studied.This can be accomplished by clear delegation of responsibility for this topic, by making clear the targets and goals and by creating an awareness of it throughout the organisation. In addition, the size of the budget (as a percentage of the turnover) says something about the importance attached to brand management. And finally, the already much discussed role of the owner plays an important part.

How these factors can all be measured in relation to each other was not the subject of this study; this is a subject for subsequent investigation. However, it is possible to give a reasonable indication of the outcome of the variables provided.

The difference with regard to multinationals lies in the fact that the vertical axis represents a logical base for them, and one that is almost always present. We do not have to impress on Philips, Coca Cola, Koninklijke Niemeyer and Nike that brand management needs to be paid sufficient attention if large scale brand recognition is to be realised. Within the SMEs people are not always aware of this, nor are the companies geared towards such a concept, because the possibilities for such companies are limited.

The quadrants of the brand development model in Figure 2 are explained in more detail below:

- I Beginning and underprivileged brands. In this quadrant it is important to make a distinction between two types of brands/companies. There are brands/companies that have just been set up which have not yet managed to create awareness and in which awareness of brand management needs to grow before it can be given a greater role. These are the beginning brands. Then there are brands/companies that have been in existence for longer but have not succeeded in gaining name recognition and have not organized a bigger role for brand management within their organization. They do not behave in an entrepreneurial fashion, they fail to embed the idea of brand recognition within their organization and they make little or no budget available for such a concept. Such brands will probably stay in the same position in the model for the next ten years. These are the underprivileged brands.

- II Emerging brands. The building of a brand takes time. Brand recognition is not something that happens by itself. Making a brand recognizable demands that a conscious effort is made to achieve such recognition. In this quadrant, the owner makes everyone within the organization aware of the need for this, gears the organization to it and makes the budget (however difficult this may be) available for it. In this regard, his/her own role as a publicist is also extremely important. The brands in this quadrant are known as the emerging brands.It is probable that a brand beginning in quadrant I will need to pass through this quadrant as its grows into an established (quadrant III) brand.

- III Established brands. If the owner and the organization of an SME are determined to build up a strong brand and do actually attain such an objective, then their brand can be considered an established brand. They have attained a high degree of brand recognition, which they maintain, and now they need to build on this to create as much brand equity as possible. In short, it is possible to reap the benefits of this success and extend it in the future.

- IV Historical brands. In this quadrant lie the brands that have managed to create a reasonable to large degree of brand recognition, despite the fact that there was little structural support for such an achievement within the organization. They are exceptions that, owing to events in the past and to the passing of time, have ended up in this position. The actual type of product probably has much to do with this. These are middle sized companies that, due to a striking product or a historical background have managed to build up an enormous brand recognition without actually having paid much attention to it. That is why brands in this quadrant can be labeled historical brands.

Recommendations for entrepreneurs and directors

The entrepreneur plays a key role in the SME and exerts considerable influence on the structure and culture of a company. The value of this study lies in the fact that it places the role of brand management firmly in an SME context and clarifies the influence of various factors.

The influence of the market is one such factor. But the influence of the entrepreneur is also extremely important: not just as the personification of the brand, but also as the individual who shapes the company structure. In addition, because of often limited budgets, a healthy dose of creativity is indispensable to the organization of marketing and communications.

What follows are a number of concrete recommendations for (successful) brand management in SMEs:

- Set the building and management of your brand high on your list of priorities. Make time available for this. A strong brand is an excellent way to distinguish yourself from your competition and, if properly applied, emphasize the quality of your product.

- Make a suitable individual within your organization responsible for the daily brand management tasks. Do not keep the management of your brand to yourself but communicate how important it is throughout the entire company. Make your business brand aware!

- Do not underestimate the (potential) role that you, as the entrepreneur can bring to achieving brand recognition. After all, you are your brand. Communicate that! It does not cost anything and the impact may well be greater than you think.

- Examine the possibility of linking your brand to another (stronger) brand. You would like to be associated with Mercedes or Bang & Olufsen, wouldn't you? So examine the possibilities for cooperation and consider co-branding.

- Is your brand more important and better known than your company name? Then consider changing your company name to that of your brand. This prevents loss of attention (and budget) and heightens brand awareness within your organization.

- Focus on one brand to prevent consumer awareness (and your budget) being frittered away on meeting the needs of several brands.

- Highlight one or two specific distinguishing product features and associate them with your brand. Focus your marketing, in as creative a fashion as possible, on these features.

- Make the logo, the packaging, the labels etc. individual enough to help with the building of the brand.

- Work consistently and be logical in all your announcements about the brand. Remember that when you begin to get bored with this, that is when the message will begin to be noticed.

- Encourage passion for the brand throughout your company. The sparks come from you, overflow onto your employees and outside the firm onto your (potential) clients.

- Check that your product displays your brand name. You would be amazed at how often this does not happen. A real missed opportunity!

- Your marketing budget is not made of elastic, something the marketers and the advertising industry rarely consider. So be creative. And if you cannot be creative, hire someone who is.

- Do you want your brand on television? But you think it is too expensive? That is not necessarily so! Especially not if you're creative and inventive and consider other possibilities than an (expensive) commercial. Think about sponsorship and PR!

- Brand management is not advertising or marketing. If you think that they are all one and the same, then take the trouble to spend some time reading the study you have in front of you now. It will be worth your while.

Recommendations for further study

The study of brand management in SMEs is still in the pioneer phase. That is why a start has been made with an exploratory study, one in which the few sparse theories available on the subject were tested in practice.

This study lays an important foundation for further investigation, one in which the three models published herein can be tested against groups of companies in the SME and, subsequently, refined. Examples of such groups would include the service sector, business-to-business organizations and small and micro-sized companies.

For the model described here, further investigation is necessary to determine an objective way of measuring brand recognition within SMEs. In addition, the ranking of the role of brand management and the weighing of various factors relating to this all call for further study.

This study has made a close, practical examination of the only model described in the business literature. Keller's model has been weighed and, in some instances, found to be too light. So new guidelines for the construction of a strong brand in an SME have been added. Only further study will determine whether these new guidelines are more applicable than those which were removed.

A study of the success of an SME, in the light of the role that brand management played within it, might well offer increased insight into the problems faced by all SMEs in managing a brand.

|

|

|

| References |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Further Reading |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Passion, innovation and fun – the secret of small business branding A recent review of business support activity in the UK observed that, for smaller businesses, the biggest concern lay with marketing. It is not that these smaller businesses are not doing any marketing – they would not be in business if they were not – but that the effort in marketing lacks professional input and expertise. And, when businesses turn to the published literature for help, they find that writing on marketing focuses on larger organizations. As Krake points out, managing marketing activity is very different where there is a department of 25 people compared to the owner/manager doing his or her own marketing. Despite the widespread view among smaller businesses that marketing is a weakness (Krake confirms this in his literature review) many smaller businesses are very good at marketing. Indeed smaller businesses tend to be far more responsive to the market and far more flexible than their larger competitors. But these businesses still look enviously at the big consumer brands and wonder how they too can achieve such awareness and provenance. Marketing in smaller businesses tends to concentrate on sales and promotional tactics rather than on the big strategic issues. Successful branding takes loads of money – or does it? Krake notes the view that branding is only for the big boys who can afford the huge budgets needed to buy lots of television advertisements and magazine pages. But we also know that smaller businesses can and do achieve success in branding without these massive budgets. Krake points out that not so long ago, Phil Knight, the founder of Nike was working out of his garage – the big brands were all small brands once. The challenge for the smaller business is how to develop a brand without compromising the need to shift product. The big brand can afford (up to a point) to throw large sums of money at long term brand building, can separate the very tactical concerns of sales management and promotion and can carry promotional failure. The small company needs to build its brand and to make the sales needed to grow the business. For many smaller businesses this need results in branding and brand strategy being sidelined in favor of a focus on sales. Krake asks whether the small business can achieve a significant shift in brand marketing without the commitment of resources the firm does not have. And having averred that this is the case, Krake then seeks to identify the central elements of a brand strategy for the small or medium sized business (although he notes that his study concentrates on medium sized businesses). The resulting approach, built on the limited work in the literature, sets out six guidelines: The advantage of the entrepreneur Big companies with established bureaucratic structures spend a lot of lime looking for entrepreneurial talent within their ranks. Employees are encouraged to “think outside the box”, to challenge established thinking and to operate across the boundaries and barriers in the firm. Mostly this is just talk – big organizations need bureaucracy to avoid descending into chaos. Processes and systems replace seat of the pants operation and the critical issue is the creativity invested in the strategy and the orientation of the business processes to deliver that strategy. Most smaller businesses do not work like this. They are creative and innovative because that is the special advantage given by the entrepreneur. This individual drives the business and everything that happens in the business is important to that person. And what that entrepreneur worries about today is the most important thing – even when it is the color of the flowers in reception. For most entrepreneurs there is no written strategy in the way beloved of business school academics. Nor is there a clear distinction between strategy and tactics – those flowers in reception are as important as the cash flow forecast (if that's what the entrepreneur thinks). And, as Krake observes, the entrepreneur becomes identified with the company – we cannot imagine that firm without its founder and leader. If smaller firms are to succeed with their branding efforts, these entrepreneurial oddities need to become part of the brand. The character of the entrepreneur becomes the character of the business and, through this, the character of the brand. Entrepreneurial brands have a different feel to them – less carefully designed, a bit maverick, not so built up. And it is this difference that allows more to be made of the brand from less money – the good entrepreneur gets more bang for his buck because of those difficult to pin down features of the entrepreneur. And the central feature is passion. Entrepreneurs are always passionate about their business. They are always ready to tell you excitedly about their latest success, a new madcap scheme or how the product they sell is so much better. Successful branding must harness this passion – the brand becomes a combination of the entrepreneur, the character of the company and the special benefits of the product. And the brand premium comes from that passionate desire to deliver the best to the customer. Krake is right – get focused, be passionate and realize that done right, sales and tactical marketing can build your brand as well as deliver the sales you need to grow. |