| H I S T O R Y |

The city of Kars is about 50km to the north-west of the ruins of Ani. As a settlement, Kars is probably older than that of Ani and, unlike Ani, Kars was never abandoned. This history of continuous inhabitation has left it with fewer surviving medieval Armenian monuments, but with many buildings from a wider time period. On this website in the future there will probably be more pages covering Kars in greater detail, including pages on the medieval castle; the 19th century defences; the districts constructed during the Russian period; etc.

For a short time (928-961) Kars was the capital of the Armenian Bagratid kingdom and it was during this time that the Cathedral, now known as the Church of the Apostles, was built. Shortly after the Bagratid capital was transferred to Ani, Kars became (in 963) a separate independent kingdom known as Vannad - the Armenian name for the Kars region. This kingdom was to outlive that of Ani.

After the Seljuk Turks captured Ani, the last Armenian king of Kars ceded his city to the Byzantine empire in 1064, getting in return the city of Amasya and lands in northern Cilicia. The Byzantines were no more successful in defending Kars than they were with Ani, and soon lost it to the Turks (in 1071). The Turkish population of Kars would have been small - but support from the Emirs of Erzurum maintained their power until 1206, when the Georgians expelled the Turkish rulers. In 1236 the Mongols occupied the region. As with other places, they probably gave a great deal of autonomy to the majority Armenian population: an Armenian prince is known to have been governing Kars in 1284.

After the collapse of the Mongol empire a series of petty Turkish emirs governed Kars until its incorporation into the Ottoman Turkish empire in 1534. In 1579 the Ottomans undertook an extensive rebuilding of the city and its fortifications to guard against Persian attacks. From the mid 18th to the early 19th century control from Constantinople had diminished to the extent that the pashas of Kars were semi-autonomous.

The gradual Russian conquest of the Caucasus, starting in the 18th century, led to an influx of Muslim migrants, especially Circassians. Kars became a strategic and heavily fortified border town protecting the Turkish empire's eastern frontier and the road to Erzurum. The Armenian population by then was probably quite small and seems to have been lived mainly in a district to the west of the old castle, just outside the city walls - there are still two ruined Armenian churches here, as well as an old medieval Armenian graveyard. The Russians occupied Kars in 1828, in 1855 (after celebrated siege lasting seven months) and again in 1877. This time the Russians kept the city.

A substantial part of the Muslim population left after 1877, choosing not to live under Russian rule. The Russians did not behave particularly favourably towards their remaining Turkish subjects; some mosques were demolished, others turned into stables, although their policy was mainly one of deliberate neglect. Those Muslims still in Kars seem to have moved to the districts formerly lived in by the Armenians. The Armenians gradually moved into an entirely new district of European-style buildings built on a grid plan to the south of the old medieval city, and most of the old city walls were demolished. There was a large influx of Armenians from other parts of Russian controlled Armenia, as well as Armenians fleeing the oppression and massacres of the Ottoman empire: Kars became a rapidly growing boom town.

In 1894 the British traveller Lynch wrote that the population of Kars was around 4000 (excluding the large military garrison), made up of 2500 Armenians, 850 Turks, 300 Greeks and 250 Russians. In 1913 the town had 10200 Armenian and 900 Turkish inhabitants.

By the end of the 19th century the Kars plain had become the home to various sects, mostly Protestant Christian, that were unwelcome in Russia proper. A few surviving adherents of one group called the Molokans are still supposed to be living in and around Kars. Some of the descendants of German and Estonian settlers still live in the Kars region, and there were also many Greek settlers, now all gone. The policy of allowing non-Armenians to settle here was a deliberate Russian one to limit the growth and wealth of the Armenian population. Lynch mentions that around Yerevan uncultivated lands were for the most part in the hands of the Russian government who were not inclined to sell or lease them to Armenians because they were keeping them for Russians.

The recapture of Kars was a key military objective for Turkey during the early months of the First World War, but their invading army was heavily defeated at the battle of Sarikamish. This defeat was due more to the winter weather and bad planning, than to the Russians (who were actually preparing to evacuate Kars).

After many more battles, Russian forces succeeded in advancing as far west as Erzincan, but the collapse of the Russian army after the 1917 revolution left only thinly spread Armenian units to resist the inevitable Turkish counter-attack. By 1918 the Turkish army was cutting a swathe of destruction across the newly declared Republic of Armenia, capturing Kars in April 1918 and reaching Baku on the Caspian sea.

Defeat on other fronts caused Turkey to surrender and withdraw to the pre-war borders. In 1920 Turkey renewed its offensive, Kars again fell to the Turks (in October 1920), so did Alexandropol. The invasion was led by General Kazim Karabekir. Significantly it is a statue of Karabekir, not Ataturk, that stands outside the Kars train station.

In November 1920 the Bolsheviks annexed the little that was left of the Armenian republic. With Armenia now under Soviet "protection" the Turks ceased their advance and even withdrew from some captured territory, including Alexandropol. The Bolsheviks wanted good relations with Turkey, and in 1921 they signed the "Treaty of Kars" ceding the towns of Kars, Sarikamish, Igdir, Kagizman, Ardahan, Artvin and Oltu to Turkey. The railway carriage in which this treaty was signed is still preserved in the Kars museum.

In 1920 much of the town's Armenian population had fled in panic before the advancing Turks. Of those that stayed, hundreds were imprisoned - and then either executed or sent to Erzurum to work as slave labour building roads. Those Armenians still free had little incentive to remain. Oliver Baldwin, held prisoner in Kars shortly after its capture, later wrote:

"If

a Turk desires any particular Armenian woman, all he has to do was arrest

the husband as a spy. If the husband caused too much trouble he was shot

at once, and the excuse was always the same: 'In 1915, when the Armenians

took Erzeroum, this man killed my cousin'. Since the poor man was dead it

would have been impossible for him to prove that in 1915 he was in

America, so the murderer was dismissed and the crime written down as

'justifiable revenge'.

One Armenian who refused to surrender a ring was murdered for it, and the

same Turkish excuse was used with the same result.

These incidents were of daily occurrence during my time at Kars, but it

was all part of the Turkish policy of seeing that no Armenians remain in

Armenia, and the consequent justification of its possession by Turkey".

The Kars Treaty enabled the deportation of the remaining Armenians. A traveller named Reitlinger visited Kars in 1931 and found most of the city deserted and in ruins, with a civilian population numbering only a few hundred. By the late 1960s the population had increased to 25,000. Today the Turkish census says that there are 78,000 inhabitants in Kars, which is now the capital of Kars province.

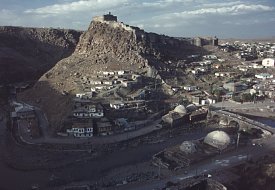

The Castle of Kars

-

-

church are now in the Kars museum